Do you know anyone who wants to write a novel? Do you know anyone who has actually done it?

I know many writers who are somewhere on the journey. It seems that the pull to write “the great American novel” is just a prevalent today as it was when the Civil War novelist John William De Forest coined the phrase.

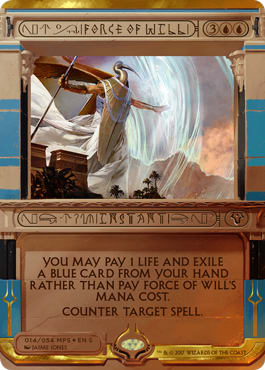

For most people, writing a novel takes time—a lot of time. There are precious few writers who actually stick it out and finish their stories. There are even fewer who possess the right mix of talent and determination to actually see their novels published. In addition to this, most novelists won’t ever see their first novels published. They often hone their craft for years, producing multiple novel-length works, notebooks full of short stories, and numerous articles before one of their novels sees publication. This is the norm for the industry. Make no mistake: Writing a novel and seeing it published requires Force of Will.

So, why would anyone do it? Why toil over a manuscript when publication is so uncertain? It’s not the money. Most novelists never are adequately recouped for the hours (read: years) they’ve invested.

Novelists do it because they are world creators—Nomad Mythmakers. They drink from the Font of Mythos and see stories in the everyday events of life.

I’m a world creator, too. Someday, I hope to publish a great novel. Most days, however, I have only a small amount of time to write. Family, friends, and the rest of life compete for my non-working, non-sleeping hours. And when I do finally carve out some time, that pesky card game we all love haunts the back rooms of my brain like a Spirit token with flying. (Haunting Misery, anyone?)

During a recent writing session (in which one part of my brain kept thinking about Magic), it occurred to me that Cube designers can have all the fun of novelists without all the hassle that comes with publication. Cube designers are world creators, too, after all. They are the J.R.R. Tolkiens of our game (or the Terry Pratchetts, if you prefer). The following article explains what I mean. Take a seat in the Story Circle, and let’s write a novel together . . .

The Plot

When a story’s plot is good, we’re hooked. We stay up too late, reading in bed, and have to drink extra coffee the next day at work. High-impact sorceries, instants, enchantments, and artifacts are the plot cards of your Cube. Select the right cards, and you’ll find yourself lying awake at night, thinking about the combo possibilities. Renowned writing teacher and literary novelist John Gardner said that plotting is “the hardest job a writer ever does.”1 But rest assured it’s a bit easier for Cube designers.

Cube-worthy sorceries, instants, enchantments, and artifacts will typically alter the playing field in unavoidable ways. Whether it’s an Earthquake, a Howling Mine, or ye olde Night Soil, these cards affect the story of the game. In a book, plot twists determine character actions. Likewise, good plot cards in your Cube will change the way your characters (creatures and planeswalkers) interact on the battlefield.

Obviously, this isn’t a hard-and-fast rule. Mundane sorceries such as Ponder still need to be included in your Cube in order for it to play well. But as a Cube designer, you have the power to create a unique plot for your Cube. (Or a Disturbing Plot if you prefer.)

Have you ever read a boring story? Have you ever participated in a boring Draft? I’ve done both; neither is fun. Science fiction novelist Orson Scott Card said, “When readers pick up your story or novel, they want it to be good. They want to care about the people in your story . . . that honeymoon with the readers lasts about three paragraphs . . . within that time you need to give the reader some reason to read on.”2

Cubes have the same short honeymoon period. When I first designed my Pauper Cube, it had too many Fog effects (Fog, Holy Day, Foxfire, Spore Cloud, and Respite to name a few). It was boring to play. Too many games dragged on. My plot sucked. I later removed almost all of the Fog effects, and that accelerated gameplay. Now when the Fog rolls in on my Pauper Cube, it’s a welcome twist in the game’s plot rather than a snooze-inducing redundancy.

The Characters

Every great novel is inhabited by compelling protagonists and antagonists. If Ebenezer Scrooge wasn’t such a tortured guy, Charles Dickens probably would’ve written A Christmas Carol about someone else. Can you imagine Moby Dick without Captain Ahab? Or The Chronicles of Narnia without the enigmatic Aslan? Of course not.3

Every great Cube will be inhabited by compelling creatures and planeswalkers. (Though there are some exceptions out there.) But since Magic is a game focused on planeswalkers and creatures, the task of narrowing down a list for your Cube can seem daunting. To help make decisions, I’ve enjoyed referencing the Average Cubes on CubeTutor.com. These Cubes are “generated using the most popular cards selected by Cube Tutor users” and are updated constantly. By referencing these lists, I perform a quick scan of the creatures many consider the best in the format. They’re invaluable tools.

Occasionally, you might be unable to make up your mind between two similar creatures. When that happens to me, I open up Gatherer and read the comments and rulings sections on each creature. The five-star-rating system on each card provides a snapshot of the community’s feelings, and the comments or ruling sections usually reveal any combos or complications that I hadn’t thought of. Just recently, I was going back and forth between one last green creature spot in my’ ’93–’95 Cube. I was waffling between Durkwood Boars and Folk of the Pines. After reading the comments on Gatherer, I quickly realized Folk of the Pines had to be cut.

Short story writer and novelist Ray Bradbury often spoke of his characters as living beings he followed through stories.4 I’ve found the same is true in Cube design. Sometimes, the best way to figure out if a creature or planeswalker is going to work is to set it loose on the battlefield. Fortunately, unlike a novel, most Cubes are living, ever-changing machinations. So, if you don’t like where a character leads, you can always take the old Darksteel Axe to the character and put in someone else.

The Setting

Flavorful lands will make all the difference in your Cube. As a Cube designer, you select the page in Magic’s Otherworld Atlas, where the action will take place. If you think like a novelist while picking out the lands for your Cube, you will probably find yourself choosing some very flavorful cards.

It’s no wonder to me why Maze of Ith finds its way into so many Cubes. Not only is it a great card, but the top-down design makes it a great setting for the battlefield. Niv-Mizzet, Dracogenius couldn’t have designed a more confounding labyrinth. (He tried, actually. Unfortunately, Maze's End will probably never enjoy the same game-changing reputation as Maze of Ith.)

Here are some other flavor-filled lands that can really draw the map for your Cube. Each one of these is screaming for a story to be told about it.

- Cathedral of War

- Contested War Zone

- Dark Depths

- Grove of the Guardian

- Hall of the Bandit Lord

- Lake of the Dead

- Meteor Crater

- Mystifying Maze

- Stalking Stones

- Winding Canyons

And this list barely scratches the surface. Go to Gatherer, and search for all of the land cards. When you resurface, five hours later, I bet you’ll have more than enough good ideas for how to create an interesting setting for your Cube.

Theme

There are many ways you could stretch this Cube-as-a-novel metaphor. For the sake of space, I’ll do a little thinking on just one more: theme. Think back to your high school lit classes for this one. A literary theme is “the central topic a text treats.” A book is well on its way to being considered a great American novel when it has thematic resonance.

- Most Cube designers create power-fueled Cubes, filled with mythic rares and broken cards. In recent years, Pauper and Peasant Cubes have also become popular, highlighting a theme of power in relation to rarity. But what about less obvious themes?

- Drew Sitte likes to revel in the past.Eric Klug designed a Cube that relives the immortal fight between the living and the undead.

- Adam Styborski says of his Cube, “Common Cards, Uncommon Excellence.”

- Ethan Fleischer built an Unpopular Cube.

- This Cube has a theme I’d call “turn one” because it’s entirely comprised of 1-drops.

- This guy wants every Cube Draft to end with people vomiting on the floor. (He’s the Hemingway of the Cube Draft community.)

What themes can you think of? What great Cubes are out there that haven’t yet been built?

Is there an “eternal life Cube” somewhere out there? One filled with Vampires, life-gain cards, and cards referencing heaven (or hell)?

What about a snow-covered Cube or an un-Cube. Surely those have been done, right?

I’d love to see a “The Hills are Alive!” Cube, filled with cards that animate lands . . . a “Rise of the Machines” Cube, which absolutely breaks metalcraft, affinity, and artifact combos . . . or maybe even a Cube called “Eve’s Revenge,” which stacks the power in favor of female planeswalkers and female creatures. (I feel that MJ Scott should probably be the one to design this Cube. Who else could do it better?)

The possibilities are only bound by our imaginations.

Do you want to be a world creator yet? Like a novelist, do you want to create a universe filled with compelling characters, unforeseen plot twists, and interesting settings? Imagine if all of those elements came together. Think of the thematic resonance you could create in your own Limited environment!

John Gardner said that “ . . . for a certain kind of person nothing is more joyful or satisfying than the life of a novelist.”5 I believe that is absolutely true for Cube designers as well. It’s time to pull out your World-Bottling Kit and get started.

1 The Art of Fiction, Vintage Books, New York, NY, 1983, p. 165

2 Characters & Viewpoint, Writer’s Digest Books, Cincinnati, OH, 2010, p.19)

3 Some of the best of Magic’s characters have warranted their own novels, too. Clayton Emery’s trilogy in the Legends Cycle is a great example. Johan, Jedit, and Hazezon are excellent reads.

4 See Zen in the Art of Writing and various interviews

5 On Becoming a Novelist, Harper and Row, New York, NY, 1983, p. xxiv