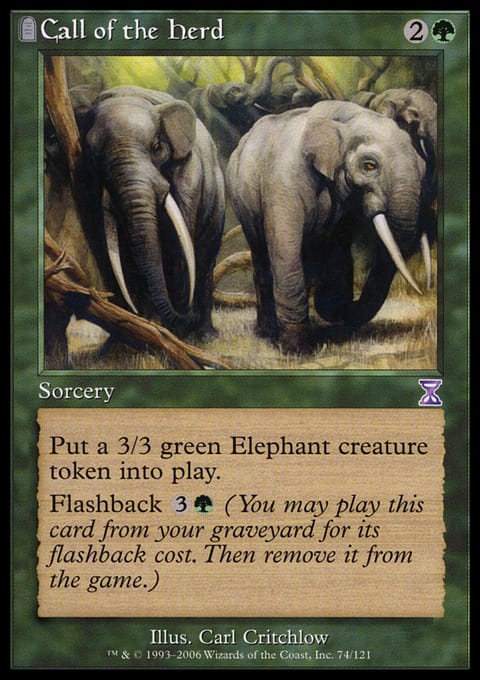

With preview season upon us there’s a lot to get excited about, but how do you evaluate new cards for existing formats? In other words, how do you look at a new card and develop some sort of context for it? Sometimes, you can compare it to existing cards you have seen before. However, this isn’t always perfect; after all, reprints that were strong in previous formats have gone on to see little or no play the second time around (Call of the Herd and Troll Ascetic come to mind).

If you’ve never played with a card before, it’s hard to know if a card is going to be good or bad. Sometimes, it’s obvious, but for the most part, many cards lie in that middle could-be-good or okay-it’s-good-but-how-good range. Of course, no methodology is going to be perfect in this respect, but if you understand how to perform card evaluation without play experience, it will improve your overall game and deck-building skills—especially in unexplored formats. The first few weeks of a new format, people will be playing untuned decklists or updates of existing decks. This is when new breakout strategies are almost always the most successful. In order to come up with those strategies, you have to have good card evaluation.

Understanding a new card has essentially two components. The first is understanding the strategic space it occupies (something I covered last week). The second is evaluating its efficiency within that strategic space. To do that, you need to understand the basics of investment theory, which I will cover here. Zac Hill wrote an old article on it here, but the ideas appear to only be semi-formed. I haven’t really heard players talking about it since—despite that it’s an important part of understanding how cards function in this game.

The Crucial Question

The question at the core of investment theory this:

What do I want out of my card?

This might seem obvious, but many times, I’ve seen people use cards (either in deck-building or in over-the-table play) inefficiently because they didn’t have attainable goals in mind for the cards they were using. Understanding the limitations of your cards is just as crucial as understanding their strengths.

It’s crucial to understand what you want out of a card—whenever you use a card, you are effectively “investing” it. This is why this is called “investment theory.” As with an investment in real life, you expect some sort of return when you make it. That return is the effect that your card has. In other words: what you want out of it.

Most people think that whenever you play a card, you are essentially investing two things: the time it takes to play it (usually in the form of mana) and the actual card. This is incorrect. You are making a third investment as well. But to illustrate this, let’s see an example.

Player A plays Plated Geopede on turn two.

Player B pays ![]()

![]() and plays Doom Blade on Plated Geopede, and then untaps, draws a card, plays a land, and passes the turn.

and plays Doom Blade on Plated Geopede, and then untaps, draws a card, plays a land, and passes the turn.

Why has Player B won this exchange? They both spent 2 mana and lost a card, so they are completely and utterly even on that part. Even so, why has Player B come out ahead, even if by a small margin?

The answer lies in the third investment you make when you play a card: its strategic investment. This is easiest to see with creatures. When you play a creature, you rarely expect for it to simply die and do nothing. Generally, most players expect to get some use out of it—some number of attacks and/or some number of activations of an ability. This is a third investment you make when you play the creature beyond the mana and card that you invest. You are asking it to perform a strategic function . . . even if that function is to simply attack once.

In the above example, Player B wins the exchange because his card, Doom Blade, has fulfilled its strategic purpose, whereas his opponent’s card, Plated Geopede, has not. Why is this the case? We return to our crucial question: What does each player want out of the card?

- Player A is asking his Plated Geopede to threaten his opponent by causing damage of some sort—either by killing creatures in combat or dealing damage to his opponent.

- Player B is asking his Doom Blade to neutralize one of Player A’s creatures.

Here we see the difference in efficacy. Player B’s card did exactly what it was supposed to do, and Player A’s card did not. This is how Player B wins the exchange. He extracted full value from his investment. This strategic purpose is absolutely crucial to understanding how exchanges in Magic work, and is thus central to understanding each “investment” you make and the return on it.

The Power of Instants and Sorceries

So, why have instants and sorceries historically been so central to the game of Magic and its formats? For years past, and to some extent today, cards ranging from Wrath of God to Blightning and Cryptic Command to Lingering Souls have shaped the Standard environment. It’s only recently that we’ve seen the likes of Primeval Titan, Bloodbraid Elf, Jace, the Mind Sculptor, and such join them. So, why did it take so long for creatures to catch up? Why were creatures underpowered for so long? The answer lies in investment theory and strategic purpose.

It’s very difficult for an instant or sorcery not to fulfill its strategic purpose.

It’s not uncommon for a creature to fail to fulfill its strategic purpose.

It’s difficult for an instant or sorcery not to fulfill its strategic purpose because it has a discernible, immediate effect on the game that is specified on the card. Thus, most players logically play instants and sorceries in spots when doing whatever it is they do is profitable. You’ve never seen someone board in Doom Blade to deal with Bitterblossom—that is obviously not what Doom Blade should be doing. The strategic purpose of an instant or sorcery is fairly obvious because it is . . . you know . . . written on the card.

The other thing to note is the immediacy of the effect. Instants and sorceries do their thing as soon as they resolve. Basically, their impact is immediate, so there really is no room for the opponent to do anything about it from an interactive standpoint. Thus, an instant or sorcery has its intended effect the vast majority of the time.

Creatures, on the other hand, are far more finicky. You need a certain number of activations or attacks for them to be profitable. Creatures can be “killed,” so to speak, not just by being inefficient from a mana perspective, but also from not regularly achieving anything useful. Thus, when you invest in a creature, you have to make a return not only on the mana and the card, but also on the strategic purpose of that creature. In other words, you have to get something out of it enough of the time that it isn’t a waste of time playing it.

Getting Stuff out of Your Permanents

Most of what I’ve said is probably not news to players. However, understanding the practical implications of it is very important. What kinds of permanents have the ability to fulfill their strategic purpose consistently?

- Permanents that are naturally resilient to removal when they hit the table. This applies to enchantments, artifacts, and creatures with static, defensive abilities such as undying, hexproof, and protection .

Examples: Strangleroot Geist, Bitterblossom, Geist of Saint Traft

- Permanents that have an immediate impact on the board, generally through triggered abilities.

Examples: Primeval Titan, Elesh Norn, Grand Cenobite

- Permanents the efficiency of which are so high that the strategic threshold for acceptable effects is very low.

Examples: Baneslayer Angel, Wild Nacatl, Tarmogoyf

These are the types of things players should be prioritizing while viewing any spoiler. Cards that fulfill one or more of these criteria should be where you start looking when you are looking to create new archetypes or new decks. Dark Ascension’s two main additions to the format (outside Lingering Souls) were Gravecrawler and Strangleroot Geist, both of which fall on this list, and both of which have had an impact on Standard.

Looking at Avacyn Restored

As far as Avacyn Restored is concerned, I really don’t want to talk about any individual card, but about a mechanic as a whole: soulbond.

What makes soulbond interesting from a strategic standpoint is the fact that it serves as added value for both creatures played before and after the soulbond creature. The other thing to note is that a good number of the soulbond creatures are rather efficiently costed—the one that gives flying costs ![]() , the one that gives Firebreathing costs

, the one that gives Firebreathing costs ![]() , and the one that gives double strike is only

, and the one that gives double strike is only ![]()

![]()

![]() . These costs are not tremendously high.

. These costs are not tremendously high.

This is really a new approach that Wizards is taking, probably subconsciously, to the problem of strategic purpose and investment theory. While soulbond doesn’t solve the my-guy-can-just-die-to-Doom Blade-immediately problem, it does lower the effective threshold for a lot of creatures. Consider that if you manage to give a single guy double strike, it’s just like getting in twice, which is pretty good in the early game. Even if he later dies to a Doom Blade, you’ve still extracted good use out of the card.

I think soulbond creatures will be better when you play them second for that very reason. Your opponent won’t always be able to plan for a soulbond-powered attack. However, if you drop the soulbond dude first, your opponent will see it coming, and that will make it less powerful. It’ll still probably be okay a decent amount of the time, but I think usually, soulbond’s ability to lower the utility threshold of the rest of your deck will be a very desirable effect.

The tension with soulbond, of course, is the fact that Day of Judgment and Slagstorm exist. The creatures spoiled so far have been small, and the ability asks you to overextend. There is a huge tempo and card cost to having your board wiped, and soulbond will have to overcome that to make its influence felt in Standard.

All in all, I am unsure of how to evaluate soulbond, but I’m definitely excited to see its effect. Constructed has a very high bar for efficacy, and soulbond attacks efficiency from a different angle. It will be interesting to see if this sort of approach is successful, and if it isn’t, what is wrong with it. I suspect if soulbond fails, it will be because of sweepers, but that might not be the case. Only time and play experience will tell us.

Chingsung Chang

Conelead most everywhere and on MTGO

Khan32k5 at gmail dot com