Prologue

If you scroll through this work quickly to find a quick fix for you, wherever you may be in your day or night, you will go wanting.

It will not happen.

This piece is not a holdover piece of fast candy; it is a long, strange trip for the discerning player/person looking to improve honestly, authentically, ideally irreparably.

Sort yourselves accordingly.

By the end of this article I hope to have presented several important - ultimately, crucial - but underrepresented perspectives on Magic: more specifically, professional Magic, various Magic formats, Magic theories, and the frameworks by which we commonly interact with one another through Magic.

Important Warning

To tackle subjects this wide, I'll be spending time on a few fairly complex topics. I invite readers to absorb or dismiss the knowledge I present as they will, but a word of caution: There's a tendency for people, especially on the internet where speaking freely comes so cheaply, to excuse new or dense information by overgeneralizing or indulging in reductionist pseudo-solutions that are only solutions at all in the sense that they pacify the disturbed and overworked mind of the wielder.

I'll provide an example.

Two people are sitting at a bar discussing sex. Both are sexually active, experienced, and comfortable with the topic. At some point in the natural flow of the conversation one of them transitions into talking about how sociology affects sexual behavior. The other person, a novice in the field of sociology, becomes suddenly aware of the sudden asymmetry between them: there is no longer "even ground" in terms of their knowledge. One of them is significantly more informed than the other.

If the less informed person in this scenario is insecure or overly instinctual, they may say something reductionist:

- "Sociology is a waste of time. It's basically just studying people. I can look at people any time I want."

- "Well, obviously sexuality is affected by sociology. One is basically just a smaller part of the other."

Reductionist statements can range from insulting and slapstick...

...to clever:

But their utility - beyond allowing someone to feel saved by parachuting out of an interaction before they face the reality of exposed uncertainty or intellectual imperfection - is virtually nil.

The more productive - and connective - act is to even out the knowledge asymmetry with questions and explanations between people. To boldly interact.

All of this is to say that you may disagree or dismiss whatever you'd like, but I would no more discuss my work with someone hellbent on lazy reductionism than a judge would allow someone in their courtroom to use The Big Bang as a reasoning for why they stabbed someone.

Onward.

Killer Instinct

How good are your Magic instincts?

Unless you're doing some card-counting style math, which almost no one in Magic does, a lot of your gameplay decisions are at least partly based in instinct. Perhaps you've tested a given deck or scenario enough to where those instincts are "honed" and your familiarity with game situations has sort of merged into a kind of informed instinct.

This is the extended version of the incredibly commonplace process that we expect to happen when we play-test: we are doing continual error corrections in order to get more evidence about how the games work - and how we win or lose them.

Typically, play-testing is gameplay as a sort of selfish scientific experimentation; its mission statement is to get a reliable sample size in an effort to get closer to the truth of a format so that you, the hardworking play-testing player, has a competitive advantage.

It was only a few years ago that a small portion of Magic writers started to demonstrate a consistent idea that they were always "play-testing" in a way - that is, that their Magic careers were always an increasing sample size building up in a greater data set than the ones that bookend a particular tournament preparation period, that the "play-testing" players talk about is only a fraction of the time spent actually working toward larger competitive truths that become increasingly apparent over years of play rather than hours or days.

That we only "play-test" during "play-testing" is an instinct. And it's obviously incorrect.

Good play-testing sessions and tournament games are only discernible by the venue in which they are being played. Good play-testing sessions happen in private homes or hotels; tournament games happen at stores or halls. The only difference in the experience of the games themselves is your framing of them based on prize support and other environmental factors.

In other words, there's no purely mechanical difference between throwing a football in a backyard and throwing a football in an NFL stadium. The distinction is in the environment and how much the thrower is affected by an awareness of it.

How much better could you play Magic if you overrode the natural instinct you have, the pressure you feel, because you know that the games streaming on Twitch have potentially different consequences than the games you played the night before on a coffee table or in a hotel lobby? Other than the way you're framing them, how are the games different?

Let's do another example.

Suppose you're in the midst of a 40-minute Magic slugfest. Games one and two finished in record time, but Game 3 is a total stall. Creatures with low power and high toughness, a few cards in both players' hands, tons of pieces that lock down other things - whatever you want to imagine a Magic log jam looks like. It has been several turns - it feels like dozens - since the last discernible tempo swing in either direction. Both players are evaluating options and shortcutting, but the draw steps aren't doing enough to move the needle in either direction.

Suddenly, your thinking takes a sharp left.

Both players have missed land drops at various turns. Your mana base is very uniform and enough of your art matches to the point it's really, really hard to honestly figure this out. There have just been so many complex things going on up until now that making land drops or keeping track of them fell by the wayside.

Now imagine the venue in which you're playing this game has a security camera pointed directly at your match. Setting aside any incidental history of tape review in competitive Magic and whether anyone is actually allowed to look at the footage or not, the fact remains that there is some documentation on the truth of whether you played a land or not.

If you're in the dark in a 50/50 scenario like this, you'll helplessly root for yourself, and by the same token your opponent will root against you. You will instinctively lean toward having not played a land, and your opponent will instinctively lean toward you already having played a land. We can set aside potentially strange card interactions that would color this as a more atypical scenario; for example, your opponent could have a card in their hand that you do not know about that punishes you for having more lands or some other such corner case. Let's go with the truism that more is better and that you would like to have another land on the battlefield if permissible.

You will have great difficulty intuiting anything except the outcome favorable for you, regardless of whether or not you can be certain it's true. Anecdotally, there have been players that are fairly reputable that have "sided with themselves" in matters that are much less foggy than this. And I would expect no one else to do otherwise.

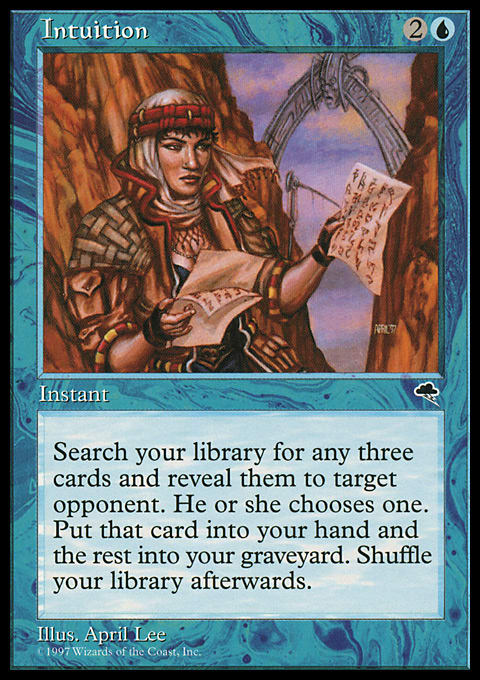

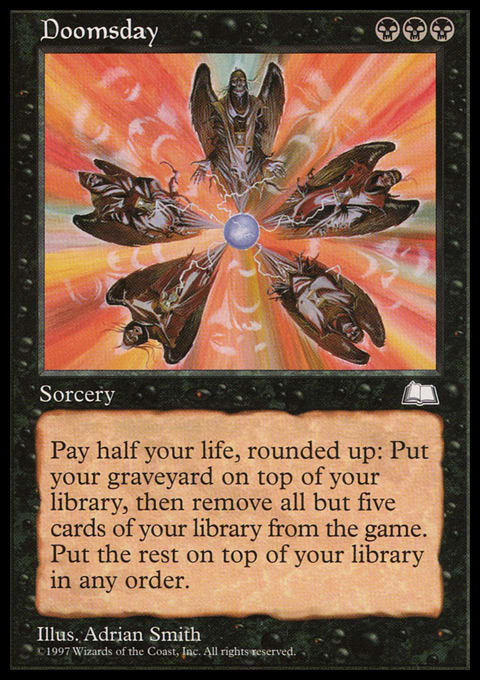

Intuition betrays us every time we open a pack and see a rare that isn't as strong as it reads in its format. It's the horrible, horrible paddling we get when Ehrnam Djinn gets reprinted in Judgment and then proceeds to 0-X every pilot that dared relive a simpler time. When our minds reflexively betray us, we see Portent and Ponder and Oath of Nissa as the same card.

And that's just in Magic.

For the overwhelming amount of human history we have been incorrect about the most fundamental truths that currently govern reality and society: satellites work because of relativity, and MRIs can find cancer growths because of quantum mechanics. Neither of these are concepts that we could intuit in our everyday lives, just as very few people thirty years ago would intuit the ubiquity of smartphones. The very air that keeps us all alive every minute of every day is transparent; we cannot see it unless it's cold or we have other instrumental means. We are incomprehensibly small all of the time, but very few people think about the scale of space except on rare occasions. If you can imagine the world before sophisticated communication systems, it would be easy to theorize large groups of primitive people that, unless they lived near an ocean or large lake, would find it incomprehensible that the world was overwhelmingly composed of water and not earth.

Your intuition is not only a subjective and unreliable phenomenon, it is overwhelmingly often an outright incorrect one. And to overcome it takes effort and willingness.

Magic: the Dispersal

What I'd like to focus on next is the most important commonality in this group of things:

- The Stack

- The Reserved List

- Mirrodin

- Planeswalkers

- Planeswalker Points

- Magic Online

- Format-exclusive products

- Errata

- Hearthstone

- Magic Arena

- Magic 2010 rules updates

These are all entities that had some population of the player base predicting they would outright end the game's life, and so far, none of that has come to pass. I would say that most of them are exceedingly unlikely contenders for the heat death of Magic at this point, and the few that are technically more likely are still very, very unlikely.

That is a lot of incorrect intuitions to account for.

Of course it's always easier in hindsight. We don't play-test so we can be better in the past. The past is a play-test. We trying to get better at predicting the future so that it most favors us.

My theory (derived from a faulty intuition valve, no doubt) is that Magic players care about Magic the way an ever-present (overbearing?) parent loves a child; it isn't so much about what is likely to happen to the kid, it's about the intuition of what could happen to the kid. That is the reason so many people fear the end that seems much more rare than you'd think given how often it is brought up.

Fortunately, again, most of these fears stop there: they're just fears. What should be of greater concern to Magic's invested audience is not what they incorrectly intuit will kill the game, but rather what forces that they aren't conscious of that could put down roots before there's a general awareness that can reverse or alter the offending, and ultimately fatal, error(s).

Mark Rosewater and others at Wizards of the Coast have talked about power creep and complexity creep as threats intrinsic to Magic's design, but there's an overlooked "creep" hanging out in the transparent margins of the game's culture that needs some spotlight.

If you're unfamiliar, in brief terms: power creep is the idea that to continue making an expanding game marketable to players there is an ongoing need to increase the power of cards until the game is incorrigibly "bloated upwards," creating game imbalance across a number of important facets. Complexity creep is the same idea, but the threatening uptick of card power is replaced instead by an ever-growing tangle of game rules that get knotted up with previous game rules and eventually reach a point that the game is too incomprehensible to either attract new players or retain existing players comfortably.

The managing of these two "creeps" is not easy, and I think it's been managed pretty unbelievably to this point in the game's history. Or at least, no matter your thoughts on where the process of managing these inconveniences to Magic is currently, it's difficult to argue that it has not been a trend of almost universal consistent improvement.

I also think they're somewhat overblown, but I will discuss that at another time.

I'll return to focus on the aforementioned "third creep" shortly.

The Fame Monster

"We know ourselves, we believe in ourselves; from what we value most, we grant ourselves the illusion that it's not chance in circumstance, that opportunity itself isn't the defining issue. We want the high ground; we want our worth to be acknowledged. Morality, intelligence, values - we want those things measured and counted. We want it to be about Us." - David Simon

Who is the greatest musical act of all-time? What is the greatest film? What is the greatest work of written fiction? Who is the greatest baseball player? Who is the greatest professional wrestler?

I'm asking a subjective agent with these questions, so we may imply a word at the beginning or end of each of these questions that is rarely (if ever) there during these kinds of conversations:

"Intuitively."

If you're in whatever defines my (our) demographic, you might answer, in order: Pearl Jam, Scarface, Ulysses, Babe Ruth, The Rock. Another set of above average answers could be: Muse, The Dark Knight, The Great Gatsby, Barry Bonds, Hulk Hogan.

Now imagine you're only eight years of age. It's easy to imagine the answers change to something along the lines of: Justin Bieber, Avengers: Infinity War, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, Bryce Harper, CM Punk.

Now imagine you're in your seventies. Let's throw out more prospective answers: The Beatles, Casablanca, All Quiet on the Western Front, Willie Mays, Jim Londos.

The purpose of this imaginary survey is not to state that liking Harry Potter makes you mentally equivalent to someone eight years of age nor is it to state that if you like The Beatles you must be in your seventies. The purpose of this scenario is to give you an idea of how limited your evaluation of "the best" is when you're limited by a given framework. In this case, the factor I'm focusing on is age, though you can imagine how various other demographic measurements (gender, race, socioeconomics, and so forth) would further stretch answers toward given groups and away from others.

Of course it's a convenient bit of generalizing, but I don't think it takes rigorous scientific eyes to accept the probability that people in their seventies are more likely to think of The Beatles and Bob Dylan as being "greater" than Lady Gaga or Drake than vice versa, and the same holds true of the inverse.

So in essence, for practical reasons, we evaluate "the best" in a given category or skill or performance not out of a field of every possible candidate, but rather out of the candidates for which we are aware. We are only aware when we are paying attention, and even then, we are only exposed to what we are permitted to be exposed to. And since it's impossible and impractical for one to account for every single film, book, and so on, we defer to experts to fill in some of the gaps and rely on the favoritism of comfortable intuition to give an answer that makes us feel good. Humans are curious creatures and it feels good to have a definite answer.

Some of you have no doubt figured out the caveat by now: that the outsourcing of that expertise is only as credible as the system itself. Otherwise, it's somewhere between curiously inconsistent on the optimistic end and complete and utter bullshit on the cynical side.

Some incidental thoughts on these different categories:

Music: Widespread music "bestness" in our culture is typically defined formally by The Grammys. As time progresses, the awards are more and more defined by more popular music due to the increasing television revenues associated with advertising. Eligible voters are largely industry veterans, meaning anything outside the realm of major entertainment recording is at this point basically ineligible to be awarded. This all sidesteps the obvious subjectivity of an experience in listening to music and what it can mean at a point in time for a given listener.

Film: Though craft experts can have a consistent view of "classic" films across basically any era, the medium of film being so accessible to everyone creates a disparity in the value of what is considered "best." Couple this knowledge disparity with some of the same structural elitism (The Oscars are The Grammys of film) and you have another cloud of indeterminate, inaccurate, and varied evaluation.

Books: Books are largely word of mouth evaluations now, rather than works widely experienced. The number of individuals, myself included, who are aware that works like Catch-22 are important or "great" far exceed the number that have taken the time to sit down to evaluate the experience firsthand. So life goes.

Sports: Baseball, and other sports, are extremely and increasingly data-based due to how profitable they are. Mythologies on their own are profitable, but without believable data, the culture wouldn't permit such mythologies to begin with. In other words, the capital forces in sports helps its credibility of potential "bests" a great deal. The profit comes not from relying on base intuitions, but rather hard-to-vary and reliable data.

Wrestling: If you're living in America, Vince McMahon's World Wrestling Entertainment has held a functional cultural monopoly on the professional industry for most of the last few decades, limiting the scope of the craft to anyone caught within the general reach of the company. The idea that Mexico could have a professional wrestling icon on the level of John Wayne (El Santo) or that a professional wrestler could achieve a legendary national status like George Washington (Japan's Rikidozan) is completely unintuitive to someone with only "carny-style" American wrestling exposure.

Our intuitions are, again, largely wrong because our frameworks are necessarily confined, not just by our own experiences and expectations but also by market forces and an ocean of other crucial incidentals that it is impossible for us to completely account for.

I choose to not use social media, by and large. How much will my opting out of these platforms affect the visibility of this article? Does how many people see it affect a single word of its accuracy or credibility?

So what does this have to do with Magic?

It's time to talk about the third creep:

Bubble Creep

Bubble creep is what I'm choosing to call the tendency for systems to unhealthily misrepresent reality due to complacent insularity.

Many systems are far too vast and have too much money to be made by too many well-resourced entities to create any authentic measurement of what determines significant cultural or experiential greatness. This enables common scenarios, such as The Grammys and The Oscars, where there is a giant sweep of natural conjecture and sharing under the collective rug under the guise of rewarding greatness that is supposedly earned but is more a question of larger factors.

Where the rubber meets the road in terms of this effect with Magic is that our measurement of great isn't just misguided, it's insular to the point of being actively damaging. It makes the Nobel Prize - another reputable icon of field celebration with more than its unfair share of subjectivity and error - seem downright infallible.

At this point I was prepared to reference what I remember to be a newspaper article from several years ago wherein the reporter, a Magic illiterate, went to see what the game was all about at a local event with often-cited best player ever Jon Finkel. Unfortunately, that article is buried beneath an internet avalanche of less useful material on a tired dating incident that should have been of nearly no consequence. Fitting!

Several years ago, on record, someone asked Jon Finkel what it takes to be the best Magic player. His answer was cited as being mostly related to luck. He provided evidence in the form of a comparison of his Pro Tour win percentage versus someone relevantly below his lifetime standing, displaying that a surprising small variation in fortune could have favored him as much as anything to do with intuitive things like him just being flat out better than everyone else.

I remember being surprised by this. In hindsight now, I realize it's not because what he was saying was inaccurate, it was because it wasn't in any way a match of the accounts that other pros had given to their success, especially at that point. I didn't realize it at the time, but it was the beginning of my realization that my visualization of professional Magic, especially the Pro Tour system, was fundamentally incorrect.

Later and for years, I became a human machine that consumed pro Magic perspectives and analysis. In my editing, I consumed roughly 50 pages or more of Magic information from the minds of pros and other similarly invested players each week for years. Ultimately, my traditional intuitions about the great Pro Tour initiative of all these years were defeated because of an implication that nobody is ever talking about.

The implication - though I'm sure it could be partially denied with various angle shootings from those that stand to benefit from the minimization of these realities - of the Pro Tour and accompanying events has been, since their inception, that hard work and dedication, over time if not outright, are values that Magic will reward, that if you just keep trying you will find validation and a life where you do nothing but Magic, that you will earn enough to place out of the infinite dregs that still just do it as a nerdy hobby. The Pro Tour is an entity to determine Magic's very best, and that can be you. You'll be different. You'll be somehow better.

This is untrue.

The pattern of player accountability that is present in so many Pro Tour player accounts (or players of similar credibility standing based on comparable events) is that you're ultimately responsible for the things you can control and that's all you can worry about. This is the sort of commonplace bridge between empowering (or discouraging) accountability for an individual player and the reality that Magic sometimes takes a few tries of you doing things right to pay off in the way you might envision. The issue is, this is such a misguided account of our perception of "what we can control" that by the time we even get to Magic, we've realized that, relatively, we don't have control over anything.

Here are a few rhetorical questions to get us thinking about scale and choice:

- What language do you speak?

- Are you a religious person? Is your faith alike or dissimilar to those in your geographic area?

- What country were you born in? What state? How far from there do you currently live?

- What is your ancestry? What are your genetics?

- What year were you born? What was the world like then, compared to now?

- Who are your parents?

- How did you get your current job?

These are intentional questions with what I hope is an apparent point, but we can also use criterion that point out more subtle blows to our intuitive view of our own reality and how much say we have in what it consists of:

- Children with divorced parents have historically been more likely to eventually be divorced in their own marriages.

- Teenagers whose parents have smoked are more likely to be smokers.

- The order of birth among other siblings (or being an only child) has reliable predictive power in describing expected future emotional and developmental tendencies.

(Philosophical sidenote: the extreme form of this view wherein nothing is technically under any individual's control is called determinism. It is the idea that starting with the earliest physical process, everything is cause and effect and thus, nothing you could ever do is outside of what was always destined to happen. I have several reasons that I don't find this point of view credible, but it is widely accepted by many brilliant minds. The only thing I wish to touch on here is that if you do to ascribe to this idea, pride and achievement - as well as shame and failure - are void by definition, since winning something, like a Magic tournament, was as preordained as any other occurrence that has ever or will ever occur. Again, it's not the table I sit at, but it is conceptually relevant.)

By the time 2019 arrived, my profession had placed me in a position to where I'd consumed, provably, more strategic Magic content - most of it written by Pro Tour mainstays - than anyone else in the world with maybe a half dozen or so others in contention. I am familiar with intelligence types, learning styles, and the like; however, it was impossible not to peg some players are significantly less versed in Magic than others despite their similar levels of success. More importantly, it was evident that the level of critical understanding one could reach in Magic was not even close to casual in determining a huge majority of events.

Here are other self-evident but unsung reasons the idea of the Pro Tour as we've known it as the marker for the best players is totally illogical:

Consider the following Magic truisms and some of their details beyond the familiar surface:

Contrast these ideas with the emergence and growth of the Commander format:

Commander is Magic's best example of a positive emergent phenomenon. Commander came not from Wizards of the Coast's business needs but rather the needs of their customer base. It was born from a substantial hole born of our antiquated ideas of what Magic has to be. If Sheldon Menery (one of Commander's major founders) had been tethered to the same intuitions that shackle usual Magic thinking, it's likely the player base would be substantially smaller today.

In the time since Commander, others have tried to create a similar phenomenon with other formats (Tiny Leaders, Frontier) to mixed reception and poor resilience. The issue is that they're trying to force emergence rather than cultivate it. They are seeking solutions that do not yet have sufficiently large problems. Commander - as well as Pauper and Modern - exist because they solve large problems that other formats do not. They are a natural emergent reaction to the needs of Magic players; they are not a contrived structure for which to sell more Magic - though part of their beauty and success is that they authentically do that as well.

Gain Reach

And therein lies the danger of bubble creep. If Magic someday becomes so insulated by intuitive, but nevertheless wholly wrong or very incomplete perspectives, emergent joys like Commander will disappear. If the tension with Magic Arena between passionate curators setting the foundation for the long-term health of the game is eclipsed by e-sports pyramid scheming, untrained wishful thinking in the player/consumer base, and investors looking to graze the next field, Magic will die. If enough players invest in the lie that pro Magic as we've known it is a mostly correct meritocracy and not the longest most boring commercial in gaming, Magic will die. If Magic isolates itself from other points of view in the games industry because it is appeasing parties whose only real priorities are to legislate themselves into professional play status quos, all in the ridiculous name of crowning patently subjective champions of nothing, Magic will die.

Imagine the now tired clich� of Walking Dead-like end of the world scenarios where a small group of people are trying to survive. The joy in these grim premises are often in assigning the useful roles for each person in the tribe. The key is diversity; a group of survivors with more unique skills will have a greater chance than a group that only has medical professionals or only has gun owners or only has people that can sew.

Magic, as a culture, from Commander to Pro Tour Standard, from Pauper to Vintage, from paper to Arena, should make its utmost priority to be openly validating of the game in ways that each player is not intuitively embracing. We have to let go of the idea that the way we interact with the game is the only way to do so and that our experiences to this point should define all of our experiences going forward. We have to preserve and protect the game from trendy capitalist tourists that are looking to take all the whale milk as quickly as they can and leave us behind with nothing to play with and nothing to talk about.

Mythic Championship winners should be rightly congratulated because it is a difficult and unique honor, not because they're definitively better than everyone else at Magic, not because there's a novelty check with a big number, and not because we're certain they are legitimately deserving of such an experience.

Magic will survive longer if we will allow it to be more than what our comforts and our egos intuit it is. The same applies for ourselves and each other.

We have to be open and willing to learn, which means we need to be more comfortable with uncertainty, even if it is not our most immediate reflex, lest we confine Magic - and ourselves - to a dangerous, specific, and very small box.

One far too confining to grow out of.