Last week, I talked about my impending future studying play and gaming and about my fears that such an area of study might one day become stifling and escapist. I followed that up by looking at some of the ways that play and games can teach us about the “serious” ways we grow and learn—pretty much (at least for me) putting those fears to rest.

This week, I will be looking at the emotional aspects of play and how they inform our lives. Children play because it fills a variety of needs—it brings them happiness, it's a safe way to explore the world, and it gives them a break from the ordinary and extraordinary stresses of being alive. I don't know who started spreading the idea that once we reach adulthood we should no longer attend to those needs, but it simply does not appear to be true.

Joy

One of my favorite moments in all the recordings related to Magic is this video. For those of you who can’t watch for whatever reason, it is the announcement of Return to Ravnica. The panelists say, “ . . . there is one thing we thought you'd want to know. But we're not going to take any more questions.”

The Return to Ravnica slide flashes up on the screen, and the audience just goes wild. Two guys jump up, high-five each other, and then hug. The audience continues yelling and clapping for a good twenty seconds—if that doesn’t seem long to you, pull up a clock and try even just clapping for twenty seconds. I started feeling ridiculous around the seven second mark.

The energy in that room was incredible. You would think they had just promised to mail us all hundred-dollar bills. In reality, they were promising something better: hope for ongoing enjoyment in the months to come.

In her essay “Play and Positive Emotion,” researcher Alyson Aborn examines research on different kinds of positive emotions. One article that she looks at attempts to define gladness—“Gladness occurs when a hope is fulfilled” (DeRivera, qtd. in Aborn 299).

Play is full of little hopes. We hope to win our matches. We hope to open something good in the Draft. We hope to top-deck a spell, or a land, or (if you’re playing Zendikar or Eventide) a spell or a land. (Our odds are good on that one). According to Aborn, it seems that play is basically practicing hope.

Lesson: A little hope goes a long way.

When I was in college, I developed fairly serious clinical depression. One common symptom of depression is anhedonia: the inability to enjoy just about anything. I was able to keep up my interest in working with kids, which took me to where I am now, but everything else just seemed like too much trouble. I cut down to the minimum schedule, I dropped my extracurriculars—my new hobby was lying face-down on the bed, taking comfort in the fact that every minute that passed without me failing a class was a minute closer to graduation.

It was around this time when I discovered Magic. This was shortly followed by board games and video games, until I was playing something almost every evening. A Draft could get me out of my room no matter how bone-tired I was. Spoiler season was the best—just feeling anything was something to treasure, much less feeling excited.

For a long time, I had thought of college as the dead zone of my life—my academics were often in the toilet, I “wasted” so much of my time and energy on playing games. I often chastised myself, “If you have the energy for gaming, why don’t you have the energy for anything else?” Later, though, the question stopped being rhetorical. “If I didn’t have the energy for anything else, why did I have the energy for gaming?”

According to researchers, positive emotions not only restore hope in trying situations, but help us to keep going. The authors argue that although direct effort to solve our problems can be important, it is equally important to take care of our emotions (Lazarus et al., qtd. in Kleiber, Hutchinson and Williams 224). Doing something we enjoy can provide us with that boost, that—in the charming words of one group of researchers—“space necessary for hope and optimism” (Kleiber, Hutchinson and Williams 226).

Safety

During a class I took on Grief and Loss, my professor talked about a type of play that she referred to as “flirting with fear.” You see this in kids climbing on the tallest tree or playing Bloody Mary at sleepovers.

Researcher Catherine Garvey referred to play as an “experimental dialogue”: interacting with the world in a tentative way. Doing something in play inherently detaches it from the consequences that come with real-life behavior (28).

When we try something new at work or at home, we risk a backlash if it doesn’t work as well as what we were doing before. For many people, that can just feel too risky. Play provides us with opportunities to try out, as Garvey puts it, “exercise of new behavior in familiar situations, or of familiar behavior in new physical or social contexts” (28). You can see this in Magic itself, as in the case of a cautious player trying out an aggro deck or an impulsive player exploring the fine art of counterspells.

Magic, and the gaming community as a whole, also provide something of an overarching play setting—if a person with social anxiety goes to a Grand Prix and becomes overwhelmed, the consequences (or lack thereof) are very different than having the same experience at a family gathering. If you try leading a team of judges at a tournament and bomb out, it’s going to be embarrassing, but you can rest assured that it probably will not harm your career.

Lesson: Freedom from reality provides a safe space to experiment.

Last year, I took a course on family therapy. The majority of the course—what everything revolved around—was role plays. I hated role plays.

I actually work best under pressure. When you have a client staring at you expectantly, choking is simply not an option. Role playing, on the other hand, brought out my perfectionism, giving me all kinds of headaches—Oh, if I had just thought a moment longer I would have come up with the perfect response.

This time around, though, through some combination of the offbeat therapy style we were learning and the professor’s dry humor, I had an epiphany. Oh, I thought, as the first session began, These aren’t real clients . . . so this is play! Suddenly, my framework switched—instead of seeing the situation through a typical therapy lens, I thought of all my favorite diplomacy games. Of Lifeboat. Of Commander.

And with that, I found the freedom to mess around a little bit. I said things that were a bit of a stretch. I even gently teased the “clients.” And while many of my classmates were still struggling with the novelty of the style we were learning, I was receiving praise for my creative and surprisingly realistic interventions.

In his book Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul, researcher Stuart Brown tells a story of how JPL was having difficulty with its new hires. They were hiring the top students from engineering schools, but those employees were having difficulty with certain practical problems that required complex thinking.

Eventually, they found that the strongest engineers weren't the ones who had graduated at the tops of their classes, but the ones who had spent time tinkering. Their skills had been massively improved by the time spent working free of expectations or consequences—by the time spent playing (Brown 10-11). Sometimes, we need that feeling of safety to be free to explore.

Escape

Escapism often seems to be framed as a bad thing—and it can be, when taken to the point that you are not dealing with your problems. But as we saw in last week's section on flow, losing ourselves in what we are doing can be a peak experience. Immersion—freedom from time, freedom from yourself—is one of the criteria defining play (Brown 17).

Life can be hard. This is obvious. What is less obvious is why some people seem to think that needs to be on our mind at all times.

When I was in college, my boyfriend and I had driven one of our friends to the emergency room for some urgent but non-lethal illness. As we both had cars, we were the de facto ambulance, and we had the routine down—grab a coat, grab change for the vending machine, grab our Magic decks and dice.

It was late at night, and the only other people in the room were two young children—a little girl of about six and a boy of about nine—no parents, just the kids. The little boy kept charging the swinging doors to the back rooms in order to try to make it past the nurse, but he was rebuffed each time. Finally, he came over and sat down with his sister to watch us play.

After a while, I started talking with the kids, and they told us their mom was in the back room and their dad was with her. The little girl mimed collapsing in the chair while the boy let one side of his body go slack—their mom had a stroke. At that point, what was there to say? I was just a teenager and worried about my own friend.

I offered to teach them to play, and they accepted. Our problems would still be there in an hour, and we could deal with them then. Until then, we could lose ourselves in the game.

Lesson: Sometimes, it’s okay to take a break.

Some people seem to find it unsettling how children can play in the wake of a tragedy. In my Grief and Loss class, we learned about how grieving adults especially may feel uncomfortable doing anything but grieving after a loss. But according to one group of leisure researchers, those children may have the right idea. Doing something enjoyable to take your mind off the problem is actually an important coping strategy (Kleiber, Hutchinson and Williams, 225).

In his powerful article “Dirty Deeds and Clean Living”, Todd Anderson tells a powerful story of how Magic kept him going while his family fell apart. Do people bury themselves in games sometimes to help them avoid dealing with the problems closing in on them? Undoubtedly. But do people also need and deserve breathers from some of the inescapable stresses of life? Of course. Doing things we love can be part of our instinct to protect ourselves, to sustain ourselves. The play instinct.

I’m certainly not the first to come up with these ideas. One of the books I mentioned earlier, Stuart Brown’s Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul is a great mainstream exploration on the positive impact of play. But as Magic players, and often as gamers in general, we are in the relatively unique position of having been shaped by play continuously throughout our adult lives.

My research has helped me to understand the way in which the qualities of play are always with me, no matter where I am or what I'm doing. And to understand the people I work with—how their playful instincts can be among the greatest resources they have, sometimes greater than anything I can offer them.

Although we choose to play our games for the joy of it, they often bring so much more to our lives as well. They can help us think, help us learn, help us heal, help us grow. Magic has led to great friendships and to great discoveries about myself and the world. It has provided a relief during some of the toughest times in my life. It has indirectly guided me to my field of study.

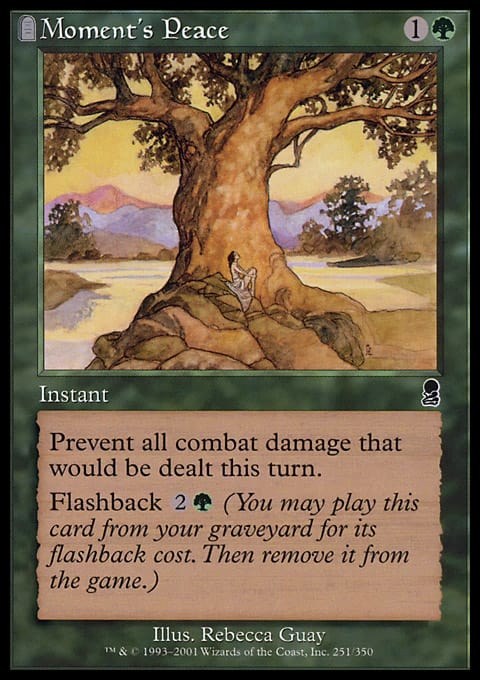

But when I first picked up those two preconstructed decks—one green and white, one blue and black—I never could have anticipated any of this.

I just thought it looked fun, you know?

Works Cited

- Aborn, Allyson I.. "Play and Positive Emotion." The Therapeutic Powers of Play. Charles Schaefer. Northvale, NJ: Jason Arnson Inc., 1993. 291-307. Print.

- Brown, Stuart. Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul. Enlarged Ed. New York: Avery, 2009. Print.

- Garvey, Catherine. Play. Enlarged Ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990. Print.

- Kleiber, Douglas A., Susan L. Hutchinson, and Richard Williams. "Leisure as a Resource in Transcending Negative Life Events: Self-Protection, Self-Restoration, and Personal Transformation." Leisure Sciences. 24. (2002): 219-235. Web. 23 Feb. 2013.

- Knocked Up. Dir. Judd Apatow. Perf. Paul Rudd. Universal, 2007. YouTube.

- Rosewater, Mark. "Nostalgia vs. Innovation." Daily MTG. Wizards of the Coast LLC, 15 Oct 2012. Web. 25 Feb 2013.