Barbarian Class!

-old combat adage

The above has been attributed to everyone from Emerson to Hemingway; and applied to processes as disparate as police stakeouts, waiting for "your spot" at the poker table, and earning a PHD.

Today, of course, we will talk about patience in the context of winning more at Magic: the Gathering.

What is Patience?

A general definition might be the capacity to accept trouble or suffering of some sort - most probably delay - without getting angry or upset. In Magic, anger or upset is probably translatable to any kind of emotional reactions instead of EV-maximizing ones; especially those that catalyze action where inaction (or further patience) will increase your likelihood of victory.

Patience might manifest as anything from passing on a good play because you know a great one is waiting further down the line; or the discipline to not use a removal card in Limited because you know for certain you can't beat the opponent's bomb rare creature - that they haven't drawn yet - without it.

I was once play-testing Vintage The Deck with Dr. Michael Pustilnik, PHD - one of the most broadly decorated Magic: the Gathering players of them all - and asked him why he didn't spend a Swords to Plowshares on whatever the opponent had just run out, relatively early in a game.

"It's irrelevant," MikeyP said; I guess kinda sorta invoking the mantras of Ben Rubin or Jon Finkel.

My thought process was that MikeyP was playing a deck with lots of velocity. Lots of Tithe-types; Brainstorm-types. He was going to run through his deck at greater speed than the opponent, and would have the ability to recycle something as trivial as a one-for-one removal spell later, if he had wanted to. To me, not using a card that could so easily be replaced (albeit not necessarily with another removal card) and leaving mana unspent was not maximizing his resource potential.

I don't think Mike ever even cast the Swords before assembling his combo-control critical mass. But whatever I wanted to remove, lost now to the long mists of memory, was irrelevant to his ability to put together the kill. Maybe if it had been something like a Hypnotic Specter, capable of tearing up the turns Mike was planning for in the future, he would have reconsidered.

At the time, all I saw was unspent mana; but MikeyP was just being patient.

The most personally impactful manifestation of Magic patience I ever experienced was watching my then-teammate Brian Kowal play in the last round of Day One of Pro Tour New York 2001.

John Shuler and I had split 1-1. If BK took his down, our team, Righteous Babe, would make Day Two. If he lost, it would be just another revolving door back to the PTQ grind. BK had gotten his ![]()

![]() opponent to three, but that pivotal last game was starting, painfully, to slip away.

opponent to three, but that pivotal last game was starting, painfully, to slip away.

Kowal had put on a lot of pressure early - hence the three life on the other side of the table - but as ![]()

![]() decks do, the opponent was starting to build advantages. He was piecing together a better battlefield. Width. Flying. Brian was either never getting through on the ground again, or it would take a lot of fading on the part of the opponent to accommodate some future, desperate, attack.

decks do, the opponent was starting to build advantages. He was piecing together a better battlefield. Width. Flying. Brian was either never getting through on the ground again, or it would take a lot of fading on the part of the opponent to accommodate some future, desperate, attack.

And then, a miracle:

Brian drew Magma Burst!

"Yep," I thought to myself. "That does three."

Even more miraculously? Brian didn't cast it.

He passed the turn. He took an attack on the jaw. The battlefield was getting worse and worse. Another attack. The opponent was going wide!

In those days you couldn't talk to your teammates during a match. Thank God! I would probably have been screaming for BK to Burst him, giving up whatever information edge the Righteous Babe was protecting. Why is that Magma Burst still in your hand, Burger King?

Then, inexplicably, Kowal drew something else relevant... And didn't cast that, either.

Another attack. Wow, this is going terribly. Why is Brian casting nothing?

Finally, on what would have been the final turn, the future architect of Boat Brew summoned something semi-relevant. Who even knows what it would have been? Some 1/1 Birds? A Reach blocker?

The opponent, presumably imPatient, cast Absorb. Not only would he get through for lethal on the next turn... He'd have a three point life buffer!

Only - you know already - the opponent absolutely did not. Having drawn out the Absorb, BK calmly responded with Magma Burst to the face before its life gain could resolve. And no, given the presence of permission that can interact specifically with kicked cards, Brian also just did the one target.

That display of patience is etched in my memory like acid on steel. The vast majority of players in BK's position would have slammed the Magma Burst as soon as it hit their hands. I know I would have! We were playing sealed deck. How did he even know his opponent had Absorb?

"The reality is," he would later tell me. "He was going to have something. Absorb is obviously the worst, but almost anything beats us in that spot. I needed him to not have 'almost anything' to resolve that Magma Burst... Because otherwise? We're not Day Two."

I think upwards of 99% of players would have not been Day Two in Brian's spot. Including myself! And I was literally Day Two as a result of his patience.

Patience is the Anti-Curve

I was playing the last round of my first Star City Invitational against nemesis Dave Shiels. Dave and I had met just a few weeks earlier, both on the same archetypes.

Shiels had gone from winning the highest skill tournament of all time - Grand Prix Dallas, with 32 Preordains and 32 copies of Jace, the Mind Sculptor in Top 8 - to losing in the elimination rounds of a New York City $5k against me... With my then-new deck: ![]()

![]() Splinter Twin.

Splinter Twin.

We were 1-1 in the rematch, Dave once against on ![]()

![]() Caw-Blade and Our Hero once again on Splinter Twin. I had Dave on the ropes... So probably a bit too much confidence... Not enough imagination.

Caw-Blade and Our Hero once again on Splinter Twin. I had Dave on the ropes... So probably a bit too much confidence... Not enough imagination.

We both had six mana. I had the choice of casting Jace, the Mind Sculptor with Mana Leak open, or tapping out for Consecrated Sphinx. I had spent all that $5k destroying Caw-Blade players with Consecrated Sphinx, and tapping out for Blue flyers is - let's be honest - pretty on-brand for me.

And plus? I knew Dave didn't have a Counterspell. Whatever I cast was going to hit. He did have a naked Batterskull from earlier in the game, and an Inkmoth Nexus... But I figured that drawing three cards per turn was going to be good enough. Even if Shiels had a Jace, the Mind Sculptor to bounce my Sphinx, I'd get two cards out of it first. Literally not enough imagination.

Did I mention I knew he didn't have a Counterspell?

From that spot, Dave embarrassed me.

On his upkeep, before drawing any cards that would trigger my Consecrated Sphinx, the Grand Prix Champion sent it back to my hand with Into the Roil. Everything fell apart from there. If you picked the square where Inkmoth Nexus would eventually suit up and poison me for a bazillion... You picked one that was a) not in my range of realistic outcomes, and b) the actual outcome of the game.

Patrick Chapin, my good friend and future collaborator, shook his head and walked away. "After all this time, after all these years, you really do just tap all your mana on your own turn if you can."

What was wrong with my play?

We know it's wrong because I had Shiels on the ropes with a commanding opportunity to put the game away and instead I got all my stuff countered by a player I knew had no Counterspells and also died to poison damage requiring a truly acrobatic amount of main phase mana tapping in a Blue quasi-combo mirror.

I've thought about this game a lot for the last dozen or so years. I think it comes down to this rule that most of us play by, which is that you really are supposed to tap all your mana every turn if you can. I guess unless you have a good reason not to. Jace with Mana Leak up was probably a good enough reason not to.

Aaron Forsythe says that getting to the elite levels of Magic is ultimately about un-learning general rules; or at least knowing when to not apply what would otherwise be best practices. My imPatience against Dave is a good example of failing on this point.

Making the leap in performance goes hand-in-hand with Aaron's thought process, most specifically where patience and mana curve clash.

-Joey Pasco

Repopulate and the King of the Fatties

My old broadcast partner and relatively recent Red Deck convert Joseph Americ Pasco sent the above to me while we were workshopping Finding the Three Gears. His quote - text really - was what catalyzed this article.

Certain sideboard cards, it seems, get false positives as a result of poor - specifically impatient - play on the part of the opponent. As long as opponents keep playing into them, the sideboard cards look spectacular. But as soon as they understand that they can play around them by adjusting their own strategies (which sometimes means simply with more patience themselves) the sideboard cards get real bad real quick.

This is exacerbated by the fact that we all tend to overvalue hands that include sideboard cards, or put additional weight on sideboard cards relative to every other land or spell in order to carry a game.

Here is an ancient example:

Jamie Wakefield was the King of the Fatties.

He stood out in the early days of the Pro Tour with every kind of clunky Baneslayer Angel from Balduvian Hordes to Morinfen; but was most famous for being the first person to lace together Natural Order and Verdant Force.

The problem for Jamie was not only that his thinking had become sort of one-dimensional... But that at some point he didn't even have the best Verdant Force strategy.

Jamie felt kind of a personal bruising when his beloved Green was co-opted by Black; and a card like Survival of the Fittest started to be better used to fill the graveyard rather than just select the best fat creature to be hard-cast for the job at hand. In those days, a common strategy was to use Survival of the Fittest to make a huge Living Death; often with the help of Fallen Angel to put creatures already in play into the graveyard for even more oomph. Thus Living Death could be made woefully one-sided.

Eventually, Jamie happened on this:

Repopulate was great!

If he didn't have cause to use it, the King of the Fatties could just cycle it. But in the event the opponent was gearing up for a giant Living Death? He could not just effectively Counterspell the opponent's ace; he could set them many manas back in their graveyard development. Perfect, right?

If the opponent was going to donkey straight into a Repopulate like some kind of Deflecting Palm or Skullcrack, then everything would go swimmingly. He'd have a story for his next edition of Tournament Reports about how the underdog Green deck could skillfully and strategically outmaneuver the dastardly overpowered opponent. And certainly it worked... Sometimes.

The problem is that with cards like these:

And creatures like these:

... The opponent never really had to go for a big Living Death turn. A patient opponent could just use Survival of the Fittest to find the perfect bullet for the situation - often a simple Terror with echo - and snipe Jamie's biggest threat. Patient play might just be chip-shotting de facto one-for-ones (that were really two-for-ones) for several turns; maybe attacking for one in the air a few times; never playing for the full combo but cornering the Mono-Green opponent to topdeck mode with some judicious 187.

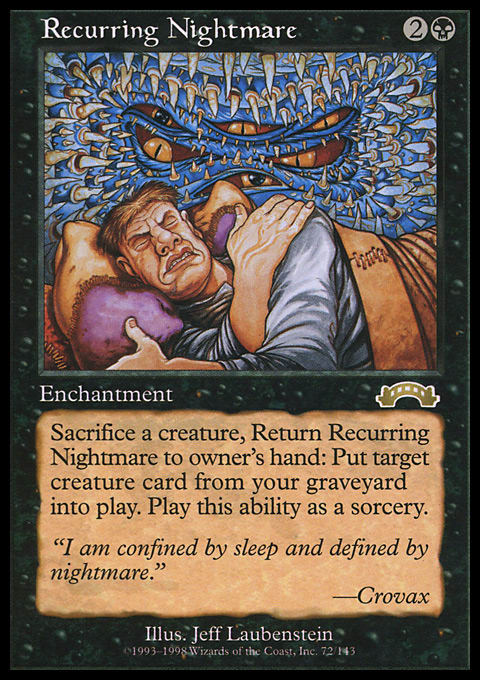

What was Repopulate going to do in that position? Force the opponent to tap ![]() one time? It wasn't even a good use to trade with Recurring Nightmare.

one time? It wasn't even a good use to trade with Recurring Nightmare.

If the opponent went all-in for Living Death? 11/10 that turn. At least 7/10 if you considered all the work they'd have to do to rebuild. Jamie would still have to do something back, and a two-mana enchantment that would go on to be banned in Legacy would still be threatening from the other side.

If the opponent didn't go all-in on Living Death? It would just be death by a thousand cuts. And for certain Secret Force would not be equipped to drag on an attrition game over many, many turns.

Even Kenji Tsumura...

The failure of Repopulate as a sideboard card is simple: It works mostly when the opponent cooperates in playing impatiently. If the opponent plays patiently, its value is lessened. It's certainly not 11/10.

Another question for Jamie might have been what he could have done at all? His main deck matchup was behind (again, he would be the second-best Verdant Force deck at the table against a ![]()

![]() opponent). He'd have to try something, right? Maybe for a big tournament where his Repopulate technology hadn't yet been revealed (let alone written about on the USENET forums) he'd have been able to catch even a Pro Tour champion.

opponent). He'd have to try something, right? Maybe for a big tournament where his Repopulate technology hadn't yet been revealed (let alone written about on the USENET forums) he'd have been able to catch even a Pro Tour champion.

Just as getting to the higher levels is about un-learning general rules... I don't know that there is a general rule to exploit here. How do we cure impatience? Can we exploit the impatience of our opponents?

Rather than rules, let's conclude with two tools.

- Imagination - On at least two occasions in my career I have had the conscious thought "I can't imagine how he gets out of this" right before he got out of it. One of them was Shiels and the poisonous Batterskull but another cost my whole team a PTQ Finals. Steve Sadin hadn't lost a match all day but needed me in the last round. I couldn't imagine losing, so I settled for the classic "good" when my opponent found truly "great". If the opponent can imagine a way out of your trap that you can't even conceive of... They might not be able to pull it off but at least they know you're not going to be in position to counter them.

- Playing "the man" instead of the cards - We talk almost exclusively about how to beat some deck or some strategy with a particular deck or strategy; but an even greater level of strategic dominance is playing against the opponent directly. What do you think the opponent is going to do? If you have a good answer for that, your counterplay is better informed. If you think your opponent is going to draw a card off your Goblin Guide trigger and then Unholy Heat it... Maybe don't play so impatiently. Maybe hold the Guide in favor of a Rift Bolt. Maybe strand his mana for a turn instead. Even the great Kenji Tsumura can be walked into a Force Spike.

If there is a cure to impatience, it is this: Flexibility.

Just not making the scripted, curve-dictated, play is a showcase in flexibility. You simply didn't do what everyone else would have done; what would have been expected. Look at how flexible!

As an exercise, think about how - right now - you can find plays where not tapping out on curve for the good play actually gives you greater flexibility toward a better one. Examples include Osyp Lebedowicz leaving up Mana Leak on turn two instead of tapping out for Izzet Signet (so on turn three he could play Izzet Signet, still leaving up Mana Leak) or Jon Becker not casting Ramosian Sergeant turn one, so he could protect it with Wax // Wane, as outlined in The Ten Greatest Battles of All Time.

When your opponent responds with the scripted play - or as I like to think about it, the play you patiently waited for - you get your spells to land the way you planned, and are that much more likely to win, even when facing an uphill battle.

So, is patience "better" than curve? No. It is the opposite of curve. Flexibility, and that elusive pathway to an elite level of play, asks you to select the right tool for the right job at the right time. I'm simply telling you - from experience as much as anything else - that curve is not the right answer 100% of the time; and will rarely produce distinguishing plays.

Afterward: I'm Pretty Sure Skullcrack Has Always Sucked

I won my first PPTQ with Modern Burn way back in 2016. So far back that I not only didn't hate Skullcrack yet, but I played both Skullcrack and Deflecting Palm on top of four main-deck Atarka's Commands. I'm not proud of it! But at least I didn't play Wild Nacatl.

When Goblin Guide first debuted more than a decade ago I famously claimed it was Constructed Unplayable. My daughter, who comes from a chess background but at that age had no concept of "card advantage" thought it was the best creature she had ever seen. "It gives you information. It turns Magic into chess. You can always make the best play."

History is pretty clear about which Flores was right on this count.

So anyway, I'm playing in the finals of this PPTQ. It's a Burn mirror. I'm three colors because Inspiring Vantage hasn't been printed yet and my opponent thinks he has the edge because he's Mono-Red, so will take no damage at all from his lands. He is, however, taking lots of damage from my Goblin Guide.

It is in the waning moments of this PPTQ that I am so thankful for the card analysis of a Bella Flores who was five years old at the time that Zendikar was first published. You see, I could see that my opponent drew Skullcrack. And another Skullcrack.

I didn't yet realize how terrible Skullcrack was, but it wasn't in my deck at the time. My very helpful Guide, though, told me that the one-match human barrier between me and another trip to Utah was gripping two of them.

Like me watching MikeyP playing Vintage; like me and the Consecrated Sphinx... He just didn't want to waste the mana. So, after my Guide connected (because, you know, Skullcrack doesn't affect the battlefield), he made the perfectly understandable play of "End of your turn, Skullcrack."

I didn't have the language for it yet, but this was the exemplification of both patience, and patience's failure.

"In response," I responded: "Lightning Helix you."

Now anyone who has ever played a Burn mirror knows that even one Lightning Helix will often decide the outcome of a game; and here I not only resolved mine successfully, but also undid any small value that Skullcrack might have had in the matchup. Armed with the vital Death Star plans my Goblin Guide had smuggled off the top of the opponent's deck, I - like Bella had long earlier suggested - had the information to make the tournament-winning play. While my opponent - lousy with lousy Skullcracks and judicious to not leave mana untapped (what could be the harm?) - went the sad way of Repopulate.

Patience.

LOVE

MIKE