Today, I'm going to give an approachable discussion and explanation of Innistrad's architecture.

Every art history student encounters architecture in one of his or her required classes. I had it in college with a professor who enjoyed a solid juice box since he talked for over an hour straight, and I was entranced by his passion for Greek sculpture on the exterior of buildings. I gave up my political science major and went with history/art history as what I'd study due to his office hours. Since I was a Magic player, it was the game coming to life, as I looked at the past.

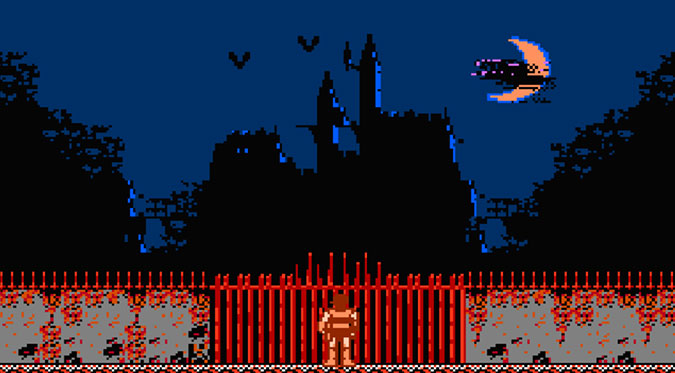

This brings us to Innistrad, home to my favorite set Dark Ascension and the upcoming release of Shadows over Innistrad, a return to the fan-favored plane. The reasons are myriad why people love this plane ever so much, and I'd like to focus on one aspect that makes it stand out visually, that being architecture.

Architecture helps to make Innistrad feel real and grounded in reality. It is our most immersive experience because we can visit it.

Concept art by Steve Belledin, Source

|  |

Images of Fachwerk in Konstanz, Germany

Images of Konstanz, Germany used with permission from Martin Zimmerman (@wortwelt) | |

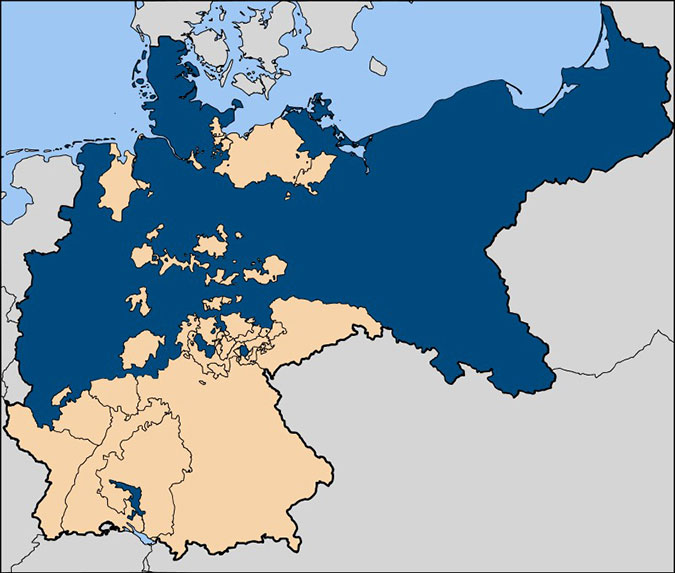

Innistrad = Prussia = Germany = Real

Innistrad was based on Prussia, an 1800s empire that spanned most of Northern Europe that wasn't Scandanavian. That "empire" visually was more Nephalia than Stensia, though it gave them a grounding in pre-Industrial Revolution Europe that was distinctly Germanic feeling. To bring it into reality, they began concept work with three very distinct German visual elements found in architecture to make it familiar yet fantastical:

- Fachwerk

- Gothic Churches

- Advanced Window making

All of the elements situate themselves from 1200s France to late 1800s Prussia. And in visiting Germany, you can see a variety of buildings and styles from each generation still to this day. Let's look at the three in depth!

Concept art by Jung Park, Source

Fachwerk, or "Half-Timbered House"

The most notable architectural element in nearly every background of anything Innistrad is the Fachwerk homes. They're the "crisscross homes" with the wood beams and white making a pattern on the exterior that were crazy popular in fifteenth-century Germany. It's a building method that was cheap, consisting of vertical, diagonal, and horizontal laminated timber beams. It's also called half-timbered homes.

Vampire Interloper by James Ryman

The space between the beams is filled with adobe, stone, brick, wood, or a variety of other materials like plaster. What makes these homes strong is that the walls do not bear the load of the roof, the beams do, allowing for strong and durable homes that last hundreds of years.

It wasn't a new architectural advance, as timber frames were around in the Roman Empire filled with plaster or wattlework, which was sticks made into a mesh. They were apt to Combust with any spark. Slow development made it into heartier homes using this timber framing. It became a "post-and-beam" construction, which helped stability and fire risk.

While we're still talking Fachwerk, did you notice the top parts of houses are larger than the bottom parts?

That seems architecturally wrong and out of proportion, right?

That is intentional and adds to the realism of Innistrad. It relates to waste management.

|  |

Crop of Hamlet Captain by Wayne Reynolds

Overhang of a fachwerk home, image of Konstanz, Germany used with permission from Martin Zimmerman (@wortwelt) | |

As we can see in Wayne Reynolds's artwork of Hamlet Captain, Innistrad has outhouses. You'll also notice that it is a fair distance from the house. This is a most recent development before populations understood the connection between sewage, groundwater, and how cholera directly connected those two. I recommend the book Ghost Map to learn how cholera spread in pre-industrial London due to a lack of education on this very matter. In short, it turns out throwing poop on the street leaked back into the water supply. Shocker!

Getting back to Hamlet Captain here, to own an outhouse meant you owned enough land, and thus wealth, to have an outdoor bathroom on your property but far enough from your home. If you were poor, you had chamber pots, which were literally pots you relieved yourself in during the night and throw it out the window into the street. (Again, that's how the human waste got there.) Now, they could use a public latrine or outhouse, but walking down two or three flights of stairs in the middle of the night, and then a block or more, was such a chore. That overhang you see? That meant pedestrians would walk next to the building to prevent having poop land on you. It's a huge deal.

In medieval Europe, every city resident or apartment owner was supposed to keep the area in front of his or her home clean, but you can probably guess how many people actually followed those laws. Sure, city sweepers existed, but they didn't have the time or budget, and even then, they occasionally would come by and push all of this garbage into the ditch. This made for a smelly street for human waste, but also for butchers, barbers, and more. When it would rain, they'd hope all would be whisked into the open ditches and carried into the nearest river. Rivers and moats in medieval Europe were so polluted that people got sick from drinking from them. Instead, they drank beer or wine at every meal. After breast milk for babies, they received watered-down wine. In Innistrad, we don't really think about all the world-building in making a real medieval world, but I guarantee you the creative team has thought of this. The overhangs show us they have.

In Magic's Innistrad, they have outhouses, which a medieval city wouldn't necessarily have, but hamlets, like our captain here, would have! They also play with this trope with Stromkirk Noble walking in the middle of the street with incredibly lavish clothing on. He's in the open, boldly showing off and walking without fear of having poop land on him due to fear and power. He need not worry. His fellow vampires keep humans respectful of their political and physical advantage.

Stromkirk Noble by James Ryman

Notice Avacyn below and the windows with the overhangs. That is world-building and architecturally correct for a medieval town.

Archangel Avacyn by James Ryman

A quick note on Innistrad's visual gag: We are not to assume this city hall, township, or "Rathaus" is bent upward. The "gag," as the art directors call them, is that humans were looking with a "first-person camera" on Innistrad to encourage a sense of personal dread. When you see a Stensian castle, you look at it if you were the human. You look up. Same goes for all the other buildings in Innistrad's first block. We will see if they fully maintain this perspective on our second visit.

Gavony Township by Pete Mohrbacher

Churches

A Discussion of Innistrad's Romanesque and Gothic

Innistrad appears to have churches and cathedrals that vary in age. This is great and actually correct. Often, you will see new games or intellectual properties try so hard to get their religious structures so based in a time period they forget that these churches took dozens to hundreds of years to create. They start at different times, end at different times, and are influenced by a variety of engineering successes and failures, like at Amiens, which we'll get to. What to remember is that churches of Innistrad vary, and that is realistic.

Before I get into how I see a variety of ages of Innitrad's churches and what to look for when looking at them, we need to cover a little bit of history on church building.

The first churches weren't really structures. They just met at a designated place and did their communal activities like worship, but they also traded, discussed news, and basically did everything Facebook does today. This is important because medieval churches weren't just for worship, they were the central places where people met.

Once humans began to build churches, actual buildings with an intention for religious experiences, they began doing so out of wood. It was cheap and plentiful. The issue was that those churches couldn't be that tall--they didn't have redwood trees for height. Since glass wasn't cheap, they needed candles and fireplaces both for light and warmth, and thus, they burned down a lot. You can see how dark the early churches could be on Innistrad from a nod below:

Blasphemous Act by Daarken

The good thing about wooden structures was that you could rebuild them rather quickly, in the grand scheme of things, and you didn't have to worry about wind.

Once churches began to be built of rocks, mortar, and stone, a gust of wind poses a problem when a building had larger walls that all felt the brunt of wind. Churches had an upper limit on how tall they could be, and to help make taller walls, thicker walls helped them from falling down. Romanesque cathedrals from the early medieval period, 1000-1200 CE are solid, massive, walled churches that are often still the largest structure in most medieval towns. Why were they the largest structure? They were a tourism site for pilgrims.

Pilgrims used to visit a ton of churches to see relics like a saint's finger, a bone of an apostle, or the like to pray to. By bringing in pilgrims, your market became more profitable. Churches were built far larger than the town would need, and relics weren't often even real, but the lure to get pilgrims and visitors to a medieval city, a serious feat, was a strong motivator.

These Romanesque ceilings and roofs were often made of wood, which still burned quite often, as attested to if you've read Ken Follet's Pillars of the Earth, you learn about this in depth. Also, if you've never read it and are waiting for George R. R. Martin, it's an incredible story of building a cathedral in a medieval town.

They used a wood roof due to its lightness. Shown below, even with a wood roof, limited the height of the walls and chamber because architects had not quite understood how to reduce outward stress on the side walls from weight and wind, even when those walls were super-thick!

Another problem kept down the size of a Romanesque church. When builders began using stone in their walls, they also used it for their ceilings. It was smoother than wood and could be painted on!

Builders formed the ceilings out of curved surfaces of stone held together by a layer of concrete. The Pantheon dome showcases this from Rome though at only 142 feet tall (43.3m), it wasn't as high as medieval builders would be satisfied with. From the roman arch, with its final keystone, builders made barrel vaults. These stone vaults were absurdly heavy, exponentially heavier than the previous iterations of wood. This vault pressed down against the stone walls and wanted to fall down. Add in our friend the wind, and churches had very real maximum heights, even with supported walls, which are called buttresses, shown below. A buttress is basically a huge stone prop that pushes in against the walls with the same force that the vaults push out. Basically, buttresses are thicker walls. Enjoy your giggle.

Image via studyblue.com

Image found on Russiatrek.org blog

With the engineering advance of the groin vault, bays (the big interior parts where a priest/bishop would stand and give a service) were possible with barrel vaults making a cross layout on the ground. We can see an example of this in Innistrad's Vault of the Archangel. The walls are thick, and it's quite dark. The walls were too thick for a large window.

Vault of the Archangel by John Avon

You can see the answer on how to make churches both taller and brighter and walls thinner below on a Romanesque church painted by Greg Staples:

Avacynian Priest by Greg Staples

The answer to this problem was the buttress itself. You can see the buttress on the exterior being intermittent pillars of stone, shown below, reinforcing columns in the latest of Romanesque churches. These outer buttresses became attached to just pillars, and then, they flew.

That new engineering invention moves the Romanesque style into the Gothic was the invention of the flying buttress. The buttress didn't really fly, but to a medieval person, they were wings. They flew to them.

Image via interactive modeling at PBS.org

How flying buttresses actually worked was that weight had to be managed better. What medieval builders did was to take the buttresses that normally pressed against the walls and move them out away from the walls. They connected buttresses and walls by a long arm or flying wing of stone. The thrust of the vaulted stone ceilings still came down the piers and walls, but also moved down the arms of the flying buttresses, down the buttresses themselves, and into the ground. This distribution of weight helped spread the weight of the vaults over more supporting stone instead of just one thick wall. You can see a version of a Romanesque buttress below on Innistrad:

To see the flying buttresses distribute weight and minimize the impact of wind, I grabbed a quick diagram below. The left is the late Romanesque; the right is the Gothic.

With the walls thinner, windows could be much larger. With the piers thinner and the buttresses farther out, more light could come through those larger windows. More light meant, quite literally, to medieval builders, a great sense of religious presence.

Image via Myartbox.org

On Innistrad, were flying buttresses present? You bet.

Bloodline Keeper by Jason Chan

If you played with the PBS interactive wall and arch modeling program, you'll notice another Gothic advancement: the pointed arch.

Let's check out Innistrad. Remember how I mentioned that it was a mix of architectural styles, not unlike reality? Check out the rounded curved arches behind Sorin.

Crop of Sorin Markov by Michael Komarck

Pointed arches were borrowed from Islamic mosques from the Moors in Spain near the Gothic period. It relieved some of the weight by directing the force more downward than the rounded arch. Round meant your keystone wanted to fall directly down, and at the 10 and 2 faces of a clock, it would add stress. By making them pointed, Gothic builders were given a tiny bit more stress relief on the walls, making for taller walls and thinner columns or piers that supported the arch. See below:

Image via sensiblehouse.org

And Innistrad also appears to have pointed arches as well:

Falkenrath Aristocrat by Igor Kieryluk

Crop of Devout Chaplain by Lucas Graciano

Windows

Let's talk windows and what they mean for architecture and Innistrad.

Building on before, the windows got to be so large in gothic cathedrals that the walls seemed to be made of glass. With forms of tracery, the stone ornamentation, windows were not load-bearing and could be entirely glass. Likewise, covered walkways could be outside the church to handle public walking flow for all the church functions that weren't a religious service, as shown below.

Konstanz Cathedral, used with permission from Martin Zimmerman (@wortwelt)

With giant walls now needing to be filled with windows, the high Gothic period created beautiful stained-glass creations that were made with individual colored glass pieces.

Or they were made of all the same colored glass if artisans were scarce and you had placeholders or during repairs, which were frequent:

Fires of Undeath by Jason Chan

In later Gothic cathedrals, these "rose windows" became enormous. Romanesque churches had them, yes, but they were small due to the weight of the wall needing to be load bearing. When flying buttresses emerged, you could have giant windows at the base of the wall or the top; it didn't matter either way. Why not make it big?

Endless Ranks of the Dead by Ryan Yee

Falkenrath Noble by Slawomir Maniak

Innistrad is logical, and that's what makes it approachable. We see Innistrad as being plausible, and in many cases, more real than other planes of floating hedrons or gods walking around with mortals.

This Brings Us to Markov Manor

Markov manner didn't care about realism, as Nahiri blew the living hell out of it. It answered the question, "How much realism do you want in your fantasy?" For a castle made for magical vampires, it's the exception to Innistrad, not the rule. Innistrad is a plane of humans, battling unnatural foes in overwhelming odds. Angels and ghosts themselves are needed for humans to combat the unnatural, unreal threats.

Geist of Saint Traft by Daarken

Olivia, Mobilized for War by Eric Deschamps

We'll talk about the impossible architecture soon in my art review.

In the meantime, save some hearts, and we'll talk again soon.

-Mike