Someone once told me that one of the best things an aspiring pro Magic player can do is learn from wins as well as losses. This past weekend, I cashed the third tournament of my Magic career—a Standard Preliminary Pro Tour Qualifier hosted by a local game store here in Seattle—and happy as I am with my results, I can’t stop thinking about one mistake I made during the Swiss.

Here’s the situation: It’s Game 1 of Round 2, and you’re playing R/W against Abzan Aggro. The game has been a back-and-forth race so far, but your opponent has stabilized with a Sorin, Solemn Visitor, bringing his life total up to 25 from 2 while you’re stuck at 4. His board includes an Anafenza, the Foremost and a Sorin at 2 loyalty; you have a Stormbreath Dragon and an Outpost Siege naming Khans. It’s late enough in the game that lands in play are irrelevant; suffice it to say that you can each easily cast any card in your respective decks, and you can pay your dragon’s monstrosity cost. Both of you are top-decking, but Outpost Siege allows you to see more cards than your opponent.

Your opponent passes the turn to you; you exile a second Dragon with Outpost Siege on your upkeep and draw a land. It’s fairly obvious that you should play the second Dragon here—there’s no point in activating monstrosity for the Dragon in play, as your opponent has no cards in hand, and it will still trade profitably with Anafenza. Plus, why let a large threat that has protection from approximately eighty percent of your opponent’s creatures just vanish into the aether? Maelstrom Pulse isn’t legal in this format. You pay 5 mana and add another 4 power to your board.

Two Dragons are breathing down your opponent’s neck, but you can’t turn them loose now—you’re at 4 life, and the only card you have in hand is a land, so you’ll need to leave one back to block Anafenza if you expect to live another turn. But what about the second Dragon? Your opponent has no cards in hand, so he’s free to take out Sorin or start chipping away at your opponent’s life total. Or he could always stay behind with his buddy and block; you aren’t in a rush to close out the game, and Outpost Siege is sure to help you win the long game. (Main-decked enchantment removal is uncommon in Abzan Aggro builds, so it’s very unlikely that your opponent will be able to disrupt your card-advantage engine.)

Your opponent has given you no indication of what’s on top of his deck (no recent scries and nothing revealed from Courser of Kruphix), so you’re left to wonder what the odds are that the top card of your opponent’s deck could be detrimental to you. No creature means game over here, as none of Abzan’s creatures has haste, and you’re just out of Siege Rhino range. The only one-sided board wipe in Standard is the unpopular In Garruk's Wake, and the only removal spell in most Abzan Aggro decks that kills your Dragon is Hero's Downfall. What do you do? Do you attack or hold back?

Trusting Your Intuition

Blink, Malcolm Gladwell’s treatise on the power of the unconscious mind, has become something of a touchstone among professional Magic players and writers. AJ Sacher, Matt Sperling, and Luis Scott-Vargas have all written about the merits of following your intuition. “I would get these feelings that my opponent had a particular card, or type of card . . . but couldn’t rationally explain why I thought that,” LSV writes. “Then, because sometimes it was very unlikely that they actually had the card . . . I wouldn’t heed that inner voice, and would then get wrecked when they did end up having it.”

That’s precisely what happened to me at the PPTQ this weekend. I hesitated for a split second after casting the exiled Dragon and reexamined the board state. The only way I could lose the game, I realized, was if I attacked Sorin and my opponent ripped a Hero's Downfall for the Dragon I left back to block. But what were the odds of that? My opponent had spent two Downfalls already, so there were at most two left in his deck. We were well into the game at this point, so assuming that there were about forty cards left in my opponent’s deck (and that’s a conservative estimate), there was only a 5% chance that he could rip a Downfall for the win. I attacked Sorin with one Dragon, convinced that the odds were in my favor, and I felt ashamed when my opponent killed the other and swung for lethal with Anafenza.

Trusting your intuition can be difficult, especially in the face of logic and probability. I consider myself a pragmatist, so my idea of the correct play in a game of Magic is the play that seems the most rational. Ignoring my intuition doesn’t seem to be working out very well for me, however—this is the second time in recent memory when I’ve made an unnecessary attack and lost after my opponent improbably had the one card that would win him the game on the spot. When you find yourself making the same mistake twice, you have to try something different.

I made the attack with the Stormbreath Dragon because I didn’t see a rational reason not to . . . but it’s possible I wasn’t examining the board state closely enough. If your visceral reaction isn’t enough to convince you to take a certain line, look for evidence that supports that reaction. I didn’t have to attack my opponent because I already had a dominant board state and a better late-game plan. I didn’t have to rush to take Sorin off the board either—blocking a white attacking creature with one of my Dragons wouldn’t cause my opponent to gain any life. Every turn I survived, I had two chances to draw answers to my opponent’s threats—and I had plenty of answers left. In retrospect, hunkering down made a lot more sense to me than making the attack.

Potential Problems

It’s always satisfying when your opponent plays that counterspell you knew she was holding, but following hunches does carry a certain amount of risk. For one thing, you’ll need to be consistent when playing around counterspells, removal, and other tricks. Imagine you’re playing an aggressive deck in a Standard tournament and you have reason to suspect that your opponent has a Wrath of God effect in hand (End Hostilities, Crux of Fate, or whatever the case may be). If you’re already ahead on board, hold off on playing out any more threats, and continue to hold off until your opponent shows you the Wrath. Your opponent may be waiting for you to commit more creatures to the board to maximize the value of End Hostilities, so don’t begin to doubt yourself if he doesn’t cast it right away. Be patient, and play exactly as many threats as you need to in order to press your advantage.

If you don’t play a lot of Standard, however, it may be difficult to tell exactly what your opponent has in hand. I was able to infer a lot about my opponent’s deck composition during my PPTQ match because I’ve played Abzan Aggro in Standard, and I also spend quite a bit of time studying decklists online. I knew that Abzan Aggro’s removal suite typically consists of Bile Blight, Abzan Charm, and Hero's Downfall—I ran a one-of Murderous Cut, but that doesn’t seem to be the norm anymore—and that even a surprise Valorous Stance wouldn’t destroy one of my Dragons. There is a certainly a downside to relying too heavily on stock lists for information, but I’ll save that for a future article.

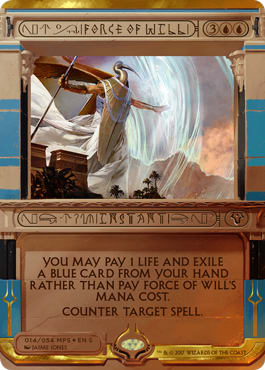

You can’t always trust your intuition if you don’t know the quirks of a format (think combat tricks in Theros block Draft or morphs in Khans of Tarkir), but occasionally, you can apply existing skills to winning games in a new format. In my second Legacy tournament of the new year, I played Delver against Miracles and won simply because I knew how to play a fair beat-down deck against a fair control deck. Fair blue decks often seem inaccessible to newer Legacy players like me, who aren’t familiar enough with the format to know which spells are worth countering at times, but when my mana-screwed Miracles opponent cast a Sensei's Divining Top, I didn’t have to think before casting Force of Will on it. I played out my threats one by one, not because I sensed an inevitable board wipe (in this case Terminus)—rather, I wanted to leave up mana for Spell Pierce to help ensure that my opponent stayed behind. There’s an old Russian proverb that says, “Repetition is the mother of learning”—the more you play a format, or a deck, or even a type of deck, the more you can rely on your subconscious to help you make the correct plays.

It’s also entirely possible that no amount of practice and rationalization will make you feel comfortable going with your gut while playing Magic . . . and that’s perfectly fine. LSV even acknowledges this in his article: “This style just doesn’t work for some people, although everyone has to trust themselves to a certain extent,” he says. “Very slow, deliberate players are often that slow because they are thinking about every possibility, and refusing to take shortcuts.” Let’s return to the Stormbreath Dragon example from earlier. As it stands, we have an advantageous board position—our Dragons blank our opponent’s threats, and we have card advantage thanks to Outpost Siege—but our life total is too dangerously low to ignore. In such dire situations, a deliberate player will take care to consider every card an opponent might draw, including Hero's Downfall, and that player will probably resolve to keep the shields up. Even when you’re ahead, always ask yourself, “What might cause me to lose the game?” (Conversely, when you’re behind, always seek out ways to win.)

However you choose to play the game, play your best, and don’t make the same mistakes I made!