I started looking at Standard a week or so before Pro Tour Khans of Tarkir—even though I, unfortunately, was not qualified. I continued my testing after the PT, as I had a local Standard 3K along with Grand Prix Stockholm to prepare for. I played various midrange decks on Magic Online, first focusing on Jeskai and later moving on to Mardu. I had a hard time getting a good grasp at the format at first since the games often seemed to end in strange ways that I did not really anticipate. After a while, I had somewhat of a revelation when I realized the crucial piece I had been missing was an understanding of tempo in the format. Even though it was quite simple, it still came as a surprise to me, and it really impacted how I approached deck construction for Grand Prix Stockholm.

What Is Tempo?

Tempo can often be quite hard to define properly, as it is more of a loose term than it is card advantage, for example. It’s easy to say that the person casting Jace's Ingenuity is getting ahead on card advantage, but it can be difficult to say who has the tempo advantage at any given point. In general, you can think of tempo advantage as being defined by which player uses his or her resources more effectively. In this article, I will discuss concepts of tempo as they relate to the current Standard environment—rather than going into more detail regarding tempo in a general theoretical aspect.

Tempo in Standard

Broadly speaking, I think there are three types of decks in the current Standard. The first type of deck tries to go under the general pace of play. This is mainly Mono-Red and other similar aggressive decks that have really low curves and try to overwhelm the opponents before they have time to play many spells. These decks often have serious problems if the game goes long, even if they manage to maintain tempo parity. The second type of deck doesn’t really care that much about tempo, and it is all about staying alive. This is mainly U/B Control, W/U Control, and some of the midrange decks that have crossed the border to control territory. A separate deck that also adheres to the same basic principle is Jeskai Ascendancy combo. It doesn’t really care what the opponent is doing, as long as it can stay alive and bring the combo online. The third type, which is by far the most popular in the current Standard environment, is midrange. I feel that in this Standard format, the midrange decks are very much about tempo, and tempo is often the defining factor in midrange mirrors.

Next, I’ll present a series of questions and then analyze each of these questions in order. I’ll also try to include some real examples where applicable. These questions are ones you should be asking yourself when you are approaching the Standard format, especially if you have not played it a great deal.

- How does tempo affect my deck-building and card choices?

- Can I overcome a loss of tempo?

- How well can my deck leverage a situation in which I pull ahead on tempo?

Card Choices and Tempo

When I first started testing Jeskai, I tinkered with various stock builds, I ended up with the version playing Hushwing Gryff, and then I started to make some changes. I imagined many situations in which Seeker of the Way was stopped by a Courser of Kruphix or Siege Rhino, and I started cutting some of them to play more impactful cards such as Ashcloud Phoenix and Dig Through Time. In the progress, I also cut a Magma Jet and some other cards for some countermagic, essentially turning my deck into a weird control–midrange hybrid.

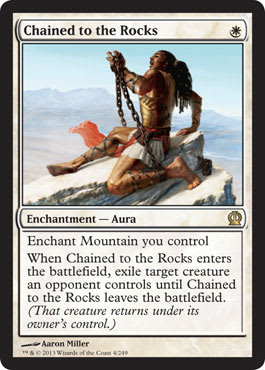

I made it to the semifinals of our local 3K Standard event, but I then lost to a somewhat strange R/W deck playing both cheap threats such as Firedrinker Satyr and Goblin Rabblemaster as well as more expensive spells such as Wingmate Roc. In the deciding game, things were looking good, as I had several impactful cards in hand, such as Ashcloud Phoenix and Stormbreath Dragon. However, my opponent had a window to resolve an Ashcloud Phoenix, and I was immediately put on the defensive, having to expend resources and time to get rid of the Phoenix. At some point, I thought I could be able to stabilize with my own Phoenix, but then my opponent played Stoke the Flames and Chained to the Rocks on the same turn, turning the game massively in his favor. I proceeded to lose a few turns later.

The lesson learned from this was that my opponent was able to use tempo to his advantage, defeating me while I still held a grip full of powerful cards. The choices I had done during deck construction came back to haunt me, as if I would have had cheaper interactive cards in that game, I might have able to pull out a win. It also showed me the real power of cards like Chained to the Rocks, allowing you to create huge tempo swings. This is part of the reason I ended up playing Mardu midrange at Grand Prix Stockholm. The list I ran was very much inspired by Brad Nelson’s build of the deck. Here is the list I played.

Mardu Midrange ? Khans of Tarkir Standard | Max Sjoblom, Grand Prix Stockholm, 13th

- Creatures (12)

- 1 Wingmate Roc

- 3 Seeker of the Way

- 4 Butcher of the Horde

- 4 Goblin Rabblemaster

- Planeswalkers (6)

- 1 Elspeth, Sun's Champion

- 2 Sorin, Solemn Visitor

- 3 Sarkhan, the Dragonspeaker

- Spells (17)

- 1 Magma Jet

- 1 Murderous Cut

- 4 Crackling Doom

- 4 Lightning Strike

- 4 Hordeling Outburst

- 3 Chained to the Rocks

- Lands (25)

- 1 Swamp

- 6 Mountain

- 2 Caves of Koilos

- 2 Temple of Silence

- 3 Battlefield Forge

- 3 Temple of Triumph

- 4 Bloodstained Mire

- 4 Nomad Outpost

- Sideboard (15)

- 3 Read the Bones

- 3 Anger of the Gods

- 2 Glare of Heresy

- 2 End Hostilities

- 1 Elspeth, Sun's Champion

- 1 Utter End

- 1 Ashcloud Phoenix

- 1 Chandra, Pyromaster

- 1 Thoughtseize

I had played a different version of Mardu previously, but the reason I really liked this version was that it had some great ways to push tempo. Chained to the Rocks is the most effective removal spell in the format as long as you can play enough Mountains to support it, and Hordeling Outburst is a fantastic threat if both players are packing a ton of one-for-one removal. Here, you can see some concessions to tempo, such as the one Magma Jet, which is often a bit awkward since there are many important creatures it does not kill. I’ll try to use this deck as an example when I am discussing tempo in the following two sections, as that way, you can form a more practical view of how tempo and various decks work together.

Loss of Tempo

Most midrange mirrors follow a very common template. One player plays a threat, and then the other player plays either a removal spell or a threat of his or her own. Due to the nature of the decks, it is often only possible to play one spell per turn until you reach the later stages of the games. This means you are not able to both play a removal spell and a threat during the same turn. It is often better to remove your opponent’s threat than to play your own, as if your opponent removes your threat in turn, he or she is able to attack you.

Sometimes, you find yourself in the unfortunate situation that you don’t have a removal spell or that the removal spell you have doesn’t quite get the job done. In these situations, it is important to identify if you can actually recuperate lost tempo. The spells that allow you to recuperate tempo are most often sweepers—or several cheaper spells acting as a cobbled-together sweeper. Let’s take two situations as examples.

In the first situation, all your removal spells cost 3 or 4 mana—for example, some combination of Abzan Charm, Hero's Downfall, and Utter End. In the second situation, you have access to End Hostilities or a combination of Chained to the Rocks and Crackling Doom. If you compare these two situations, they radically alter how you play the game and the types of strategic decisions you can make. If you do not have access to tools that let you recuperate tempo, you are forced into a situation in which you are greatly incentivized to answer each and every threat your opponent plays. If, on the other hand, you have End Hostilities, you can take a removal spell from your opponent with Thoughtseize and let him or her play Siege Rhino into Wingmate Roc and then just kill them both.

As these are things that impact how you play the whole game from the very first turn, it is imperative to identify how you have to play as early as possible. Try to deduce what deck your opponent is playing from the moment he or she plays his or her first land, and try to find clues that can tell you which version of the deck the player is running. Is this Abzan aggro, or is it more midrange, or is the opponent running a lot of Planeswalkers? These are naturally questions that require you to have a fair bit of knowledge regarding the format, as you need to be able to pick up on the subtle differences between various lists. Being able to identify the matchup as early as possible lets you know if you can afford to fall behind on tempo or if your most important task is to retain tempo.

The Mardu version I played was fairly soft to Wingmate Roc before sideboarding unless I had a good amount of board presence for myself. However, after sideboarding, I often had access to End Hostilities, letting me play in a totally different way. Instead of constantly having to stop my opponent from attacking and triggering raid, I could focus on the long game, knowing I had tools to handle a larger number of situations than I had before sideboarding. Many midrange decks in Standard work in this way, as they often transform into slightly more controlling decks after sideboard. This also means that some cards that are fantastic before sideboarding, such as the aforementioned Wingmate Roc, can become a liability after sideboarding.

Leveraging Tempo

Much in the same way that falling behind on tempo can feel like trying to climb out of quicksand, you should actively be trying to put your opponent down in said quicksand. By having cards that actively let you push the game in your favor, once you gain the tempo initiative, you are able to create a real advantage. I think the Planeswalker-heavy version of Abzan Midrange is relatively weak at this, while decks like Jeskai, Mardu, and Temur excel at it. Temur especially is a deck that is great when it pulls ahead, as cards like Temur Charm and Stubborn Denial are so good in those situations. On the flip side, it is also a deck that can have serious problems recuperating tempo if the opponent pulls ahead.

As I mentioned, I played Mardu at Grand Prix Stockholm because I thought it had great ways to both recuperate and leverage tempo. Hordeling Outburst may seem innocent enough, but I think it is one of the best ways to leverage tempo. If you are able to play a Hordeling Outburst on a somewhat empty board and then follow up with removal spells, you are putting a good deal of pressure on your opponent. Even though the tokens are small, having to deal with three separate bodies can be very tough for many decks. Even if only one Goblin is left attacking, that is still damage that is being piled on every turn and forcing your opponent to do something. This is another reason Goblin Rabblemaster is so good—since even if you only make one token out of the deal before the Rabblemaster dies, that token can still let you push your advantage going forward.

Crackling Doom is also a good card at helping with tempo, as the 2 damage dealt to your opponent can sometimes cut down your clock by a whole turn. Other times, the 2 damage can finish off a problematic Planeswalker. Crackling Doom is especially good against Sorin, Solemn Visitor, as it takes out both the token and Sorin, letting you effectively trade one for one if your opponent just plays it on an empty board and uses the minus ability.

Tying Tempo Together

I hope this article has helped you build a better understanding of tempo in KTK Standard. I realize that the concept of tempo can be tricky, and I don’t always have a perfect grasp of it myself. I think that by playing a format extensively, you build a good understanding of what is important and of when the crucial turns are during which you either pull ahead or are left behind. On a purely theoretical level, you can look at the cards different decks play and think of scenarios in which these cards interact, but nothing beats actual games if you want to understand the tempo of a format. I also think the games in which the outcome is decided by tempo are among the toughest to play correctly, as these games tend to be very close.

On the Horizon

I will be playing in a sixteen-player, Invitational-style event at the beginning of December, featuring some really strange and funky formats. I think these types of events are really fun, but also very challenging as a Magic player, so I will do a write-up on the formats in the near future. I wrote an article about a similar type of event that you can check out in the meantime.

I would love to hear your thoughts regarding tempo, as I am sure there are some contradicting opinions to mine. You can get in touch either via the comments section below or directly via Twitter.

Thanks for reading,

Max

@thebloom_ on Twitter

Maxx on Magic Online

You can find my music here.