"Man's fare in battle is worked out before the war begins."

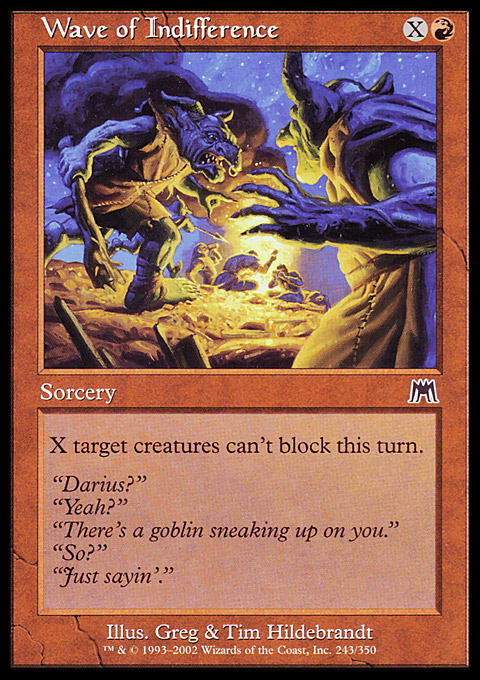

Battle for Zendikar is upon us and as a battle, not as a concluded war, we are only seeing depictions of actual battles. We have seen attacking creatures in every set since Alpha, but this set changed a few visual narratives from the normal tropes and gags. We're to read this as a battle in process, not as a finished war. It ain't over, as it were.

This set differs from Scars of Mirrodin, which was a test in the recent-nostalgia trope that Wizards of the Coast has made us comfortable with currently. While Scars and the unknown outcome of Mirrodin Pure vs. New Phyrexia had players guessing what side would prevail, the inevitable was the only choice: Phyrexia would win easily, and their victory would be absolute.

Though apparently Koth is still alive and Melira still lives with some Mirrans:

"Leading the Mirran resistance. The geomancer Koth had once said to his companion, Elspeth,"If there is no victory, then I will fight forever." True to his word, Koth adamantly spends his days protecting survivors on his corrupted home plane that once was Mirrodin, but is now the hellscape of New Phyrexia. Together with the Sylvok healer Melira, he has dedicated his life to defending those who remain."

Getting back on point, we were given a war on Mirrodin, and it ended. Wizards obviously wants to return to Phyrexia sometime and needs to leave a trapdoor out for Koth in case they need to revisit. Zendikar has no such end in sight. We are one set in, and the intentional usage of the word battle instead of war is not lost on me. This set is not going to have an end.

The other two Eldrazi titans are going to emerge, and it will fade to black. The art reflects this because it shows all the aspects of a battle, but not the traditional images of a war. It definitely isn't building up to a completed conflict. This war will span sets, blocks, and planes. Art doesn't lie, and it sets up a long conflict, not a neat conclusion.

War as Visual Trope

We see some traditional scenes of war on Zendikar, included salted earth and burnt fields on the nonbasic lands in the forms of white chalky annihilation of Ulamog's brood. The devastation is there, but many aspects of war aren't seen. We haven't seen the aftermath much; it's all so current. Some of that is a necessity of showing a figure for a tiny box that needs to describe an Elf Shaman instead of a narrative on how the Zendikari are doing in the war.

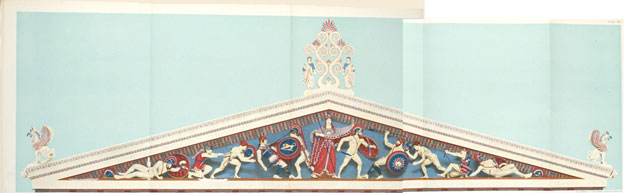

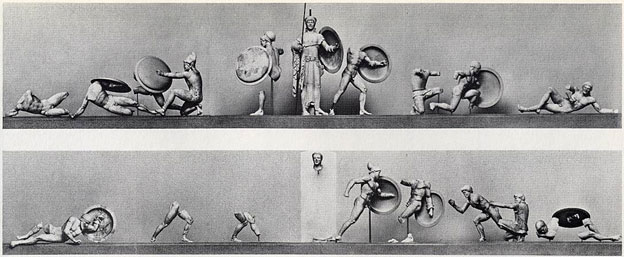

These tropes of battle scenes, of iconic historical depictions, have occurred for centuries. In fact, having paintings of war is a very, very old cultural phenomenon dating back to the Greeks. (It dates back even earlier, but the Greeks went wild with it.) A great early example is the Temple of Aphaea.

It was built circa 500 BCE and had depictions of the two Trojan wars. Midcombat is just easier to depict, as it cannot be confused for anything else. You can see the original depiction, painted with gaudy color and what are the only things left, below.

|

|

|

Image found here and Wikipedia |

Sculptures alongside temples were quite common in early Mediterranean culture. The "actual battle scenes" were shown via sequential art. Think more Egyptian narratives on walls, frescoes of naval battles, or things like the Bayeux Tapestry, a panoramic narrative of the battles and major events of the Norman Conquest and the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Paint was expensive, and painting wasn't as popular as walls, textiles, or sculpture. They didn't even have extensive use of the color purple until the 1800s, when it finally wasn't made from a snail. Seriously.

An Arbitrary Start: The Battle of San Romano - Art Diverting from Religion

To begin a conversation of Magic art and war art, I would like to begin with a favorite piece, the Battle of San Romano, as it shows a shift of many things dealing with war.

Why this piece? It's a shift. Medieval art was largely religious subjects or religious based scenes not showing war, because, among other reasons, they commissioned the art, and worldly battles didn't figure into sermons or church teachings. Unless a pope ordered a holy war, like Pope Urban II, but even then, paintings aren't common. You would think more Jesus attacking the devil and allegorical imagery would exist, but that came later during the rise of Italian renaissance painting, where I arbitrarily started.

Niccolò Mauruzi da Tolentino at the Battle of San Romano, c. 1438-1440), egg tempera with walnut oil and linseed oil on poplar, 182 × 320 cm, National Gallery, London.

As Italian city-states were always at war with one another, and this painting shows the Florentine commander without a helmet. That signifies victory. It's a conflict and unique it its creation because of a changing of style.

It was the international Gothic style, that of pattern and color from the turban to the horse decoration. But it was also something new, a contemporary examination of near perspective, showing the mathematical ability to render deep space with linear perspective (shown below).

This is a massive painting, one of three, and you feel as though you are in the battle due to their size. I've seen one of them at the Louvre in Paris, France. They're also odd in that they're a secular commission, compared to nearly everything being religious in nature. It's a depiction of war, and it doesn't involve a Greek deity, any Christian warriors, symbols for Christianity, incarnations of gods, or supernatural intervention. It's something else and something else done on a large scale, exceptionally well.

Let's compare this to the alien Eldrazi, considering I'm writing on Magic.

If Rise of the Eldrazi hadn't happened, this Battle for Zendikar set would be Magic's attempt at showing impossible to grasp beings, Eldritch Abominations.

Instead, depictions of a key pivotal event-such as on Outnumber below here-aren't that different or new. Their storyline relevance is increased, but visually, not much changes. If we had never seen Rise of the Eldrazi, this would be a fantastic new creature design. Leaning on Cthulhu mythos, these are alien and roughly known, especially as Eldrazi are seen now for the second time, making them familiar, possible to grasp and describe. We speed up cognition and can skip narratives because people know what these things are with Google searches.

Outnumber by Tyler Jacobson, digital, cropped

We know by Wizards telling us that Outnumber depicts the Planeswalker Gideon and his allies as they retook Sea Gate, but the image doesn't show us that.

For these Renaissance painters, especially in Italy, their heightened skills needed to be showcased, and since private commissions were coming from city-states wishing to glorify a winning battle or a wealthy house's victory, artists were delighted to demonstrate their skills in showing complicated poses and new styles. These Italian paintings consisted of, all things considered, minor battles, but significant to the art scene because new patronage wanted them in high demand. Think of it as a student building a portfolio, over an entire region, and everyone wants work made. Sometimes, there was nudity; other times, there were surprised soldiers in the camp or weird cavalry moments. It was radically different from religious patrons, and people loved it immediately.

Albrecht Altdorfer, 1529, oil painting on panel, 62.4 in × 47.4 in. Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany.

A piece that continues this conceptual shift is Altdorfer's historical depiction of Alexander of Macedonia's victory over Darius III of Persia at the 333 BCE Battle of Issus. It's a vertical format-an odd choice-and, arguably again, it was the best panorama battle depiction in contemporary circles at the time. The aerial viewpoint would be copied and imitated even in Magic, but not quite to this dramatic effect. Though War Report takes this concept to a devastating assumption.

War Report by Mike Bierek, digital

Were the game to have a larger image box, you could see the Phantom General here lead more of his troops instead of just a cropped view of him. When you see style changing pieces in art, they tend to be large, as to show importance, but also to showcase every intention of the patron to include in order to accomplish a painting that commemorates a historical scene. Some aspects may be embellished, like depicting battles hundreds of years later to making leaders in battle unarmored, but the scene is known, and the painting memorializes the outcome.

Phantom General by Christopher Moeller

Adding in Northern Europe: Boats, Treaties, and Heroism

Northern Europe often liked small groups of soldiers or singular figure depictions in comparison to Italy's love of city-state battles. From still-lifes to Dutch wealthy nobles, the figure was king. Though, unlike Italy and the Medici family, you could actually show a less heroic, negative view of soldiers and not fear for your life. (Well, you didn't fear as much.) Since mercenaries were so common, being a soldier and the symbols of supporting a cause or nation state could be all the commentary an artist and commissioning agent would want.

Look at these figures below, and see how varying the degree of noble pursuits or downright frowned upon, even evil deeds could be interpreted. There was incredibly variety to be examined with soldiers in Renaissance art, and the late 1600s loved to examine them-and boats. Cripes, they loved their naval-battle paintings.

The North had the Dutch Golden Age paintings to go along with their naval battles, often from atop a hill, and the 1600s were dominated by it. This went out of favor in the mid-1700s, but we'll get there soon.

Major works, like Turner's The Battle of Trafalgar, showcase a pivotal scene, but they didn't show much innovation. You can only paint so many boats with lighting changing before patrons stop paying you to do so, like in the 1800s, when you had to be super-good, or like when a patron was super into boats, such as with Turner's commission. It's also hard to show a heroic character when the general wasn't on the boat.

Joseph MW Turner, The Battle of Trafalgar, oil on canvas, 1822-24, 2615mm × 3685mm

While in the 1600s, boat battles are fun, alongside them were a ton of paintings of treaties. If you want some fame from a painting and you aren't a captain, showing the ceasefire or negotiation of surrender with the battle would allow a leader of a nation or city-state to make it on the painting.

Land-based military art is what they called it, and pieces were painted to commemorate something significant. Both sides tended to be respectfully painted, a style later disregarded in the Americas with "noble savages" and rather racist depictions of American Indians. (If you look at your local statehouse with paintings from the early 1800s, you'll see exactly what I mean. It's really quite bad.) It's less than flattering and doesn't exactly get covered in high school history courses.

Surrenders were commissioned by the victors, and if a key battle moment could also be shown, great! There are countless examples of minor skirmishes painted, just to have something to hang your hat on. It's totally small government and a "major" rezoning project that you can call a major victory.

Diego Velázquez, The Surrender of Breda, 1634-1635, oil on canvas, 121 in × 144 in. Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

You start to see more heroic-general-on-horse, not unlike our Battle of San Romano commander in the 1700s. Newer depictions showed just laughably improper dress in battle. French people loved seeing royalty in swag clothing in battle. These are still giant paintings and tend to focus in on one character, with waves of "importance" radiating away from that figure.

See Copley's work below. You see the general first and the horrific scene is so very secondary to him being all heroic-or something.

John Singleton Copley, 1783-1791, oil on canvas, 214 in × 297 in), Guildhall Art Gallery, London.

Compare Copley's work of forcing you to look at one figure to Mike Bierek's Drana, Liberator of Malakir. Sure, the difference is thousands of hours difference, but follow me here. They use a similar technique of focusing your eye to an unconcerning leader pointing folks into battle.

The central-focused character is clear, we just don't see whom the character is attacking or whom the character has defeated. Welcome to the tiny size of card art. You lose and miss a lot of narrative. In the below case, the Eldrazi aren't shown, so it doesn't tie Drana's leadership to being against the Eldrazi in a vacuum. It's an isolation that could be vampires joining to kill anything.

Unsuitable clothing for war? Drana totally agrees with you that it's unnecessary to be in battle without looking fresh. Even if you're floating, you have to have the biggest hat or people won't know whom to follow, from antiquity in art history to contemporary gaming. Big hats are always important.

Drana, Liberator of Malakir by Mike Bierek

The Horrors of War Emerge: PG-13 with Historical Accuracy

Right around this time, the late 1700s, had more horrors of war show up in "triumphant" battle scenes. Things are still successful from the victor's eyes, but casualties start showing up in art showcases.

This painting of the Battle of Valmy by Horace Vernet shows the white uniformed infantry to the right while the blue-coated ranks to the left are from the citizen volunteers, not quite mercenaries. Art begins to reflect exactly what actually happened. It's just not exactly in order or entirely historically accurate.

The Battle of Valmy, September 20, 1792., oil on canvas, 1826, 174.6 cm × 113 in. National Gallery, London.

This is a more realistic depiction of war. While stylized and very methodically organized, it shows a more honest depiction. This shift of showing dead horses, which were expensive investments, and needing reference for dead soldiers became both wanted and needed for accuracy. It was war, but it wasn't hell. It was a PG-13 movie, in essence.

This is the shift that art descriptions struggle with, even now, in media to gaming. Consider the below promotional image of Battle for Zendikar. Did it actually occur as stated, or is it just a heroic representation that was "kinda like this" for dramatic effect but had all the necessary major characters? It changes your entire experience.

Concept art of Battle for Zendikar by Tyler Jacobson, digital

The Woe of War and 1800s: Propaganda and Heroism

Comparing heroic Planeswalkers on Zendikar and the late 1700s showing some war, there were mainly heroic changes rapidly in actual history. The Massacre at Chios by Eugène Delacroix shows a calmness, a new depiction that shows a scene less chaotic than it should be for an event with ten thousand soldiers on an island. Take a few seconds to look at it; you've made it this far, right?

The Massacre at Chios by Eugène Delacroix,1824, Oil on canvas, 419 cm × 354 cm (13' 8" in × 11' 7 in) Louvre, Paris.

This Delacroix painting has something many depictions didn't have in courtly life: bodies strewn across the ground, mothers and children looking for family members, only to probably find them dead. The only representation of violence is with the two figures on the right. One woman has her hands above her head to be struck down or begging for mercy. The other could be a prisoner of war, showing a naked captive as a fate worse than death. Though the Turk doesn't look menacing, he's indifferent. He's more bureaucratic than a soldier. He's guilty for orchestrating this, but he's shedding no blood. Also, he invokes zero fear. He's human, and yet, he's not part of the scene and the humanity being poured out. Perhaps he's sympathetic to the sorrow and despair but is powerless to do anything. This was probably Delacroix's point of symbol to the French elite, ignoring their own poor and suffering fellow man. They're ignorant to the issue, and yet, the artist finds them both disgusting and displaced. Though I could be reading too much into it.

There is no right way to discuss this piece, but losing a family member, the displacing people, the violation of women, and the breaking of a culture are things any member in an organized society should feel sympathy for, as they are universal, even for a French aristocracy.

There are no heroes here, and Delacroix intended it so.

The French salon raved about the opposite perspective by Delacroix, not showing heroes but rather, the effects of war. The only comparable to Magic, is Reparations and massive wraths that show utterly Devastation:

The closest recent example Magic has are lovers who are attempting to be reunited on Theros.

A family is torn apart, meddled by gods and life's misfortunes, but we, as the viewer, do not see ourselves. We can relate to love lost, but a massive tragedy is hamstrung in a game where the card box is so small. There is also the issue of the real costs of war being near impossible to depict in a game with many younger players. True evil and an immediate visceral empathetic sorrow can't be shown. It's just too much for a game.

Reviving Melody by Cynthia Sheppard, digital

Returning to our traipse through history, while Delacroix, a master, was making works, royal subjects still needed their art, but with a little feel to it, as it were. The kings of all heroic, yet horrific works were paintings involving Napoleon.

Paintings of battle into the 1800s gained a new intention, that of having propaganda purposes. If the painting of Uccello was stylized to show victory, a new revolutionary art form, showing history and propaganda fused into one, was fundamentally French at the time.

Napoleon on the field of Eylau or the painting of Battle of Eylau was Antoine-Jean Gros immortalizing Napoleon as leader of the French. To understand how this happened, you have to realize that the Battle of Eylau in 1807 was between the French and Russian/Prussian forces. This was the first real check of power against the French army.

It lasted only two days, and it resulted in a stalemate. Both sides had casualties by the thousand. It was not a decisive victory and only could be considered as such because the Russians retreated. The Prussians were subjected to French occupation, but the Russians didn't really lose, they just weighed the option to care and didn't think it worth it. It was February after all.

Gros painted this piece, and while overt representations of violence were not permitted, artists always had to submit sketches to Napoleonic propagandists to make sure Napoleon was seen in the proper light, unmoved by the pestilence of war and in a triumphant victory. Compare this to Velázquez's The Surrender of Breda, and you see more emotion, more horrid things, but it's also less honest. It's a fabricated Instagram photo in comparison.

"Napoleon on the field of Eylau" by Antoine-Jean Gros, 1835, 5.21 m x 7.84 m (17 feet x 25 feet), Louvre, Paris.

Anything dealing with Valley Forge or George Washington is depicted similarly, with tightly controlled subjects, and only certain figures that could be included. He's a hero and the purpose sound! He's the father of America! Right? Right?

Emanuel Leutze, 1851, Oil on canvas, 149 in × 255 in. Minnesota Marine Art Museum in Winona, Minnesota.

Shifting back to Magic's Battle for Zendikar, Lake might give us a similar glimpse into propaganda as "all the allies" binding together, uniting to defeat the Eldrazi menace. Looking at Lake's piece closer, you start to see no ripped clothing, worn warriors, blood, and the unification being the only takeaway as idyllic.

You also don't see tired horses, terribly looking bread and tents. Gideon's crew is made for a poster to have you join them as allies, not show how badly they're being whooped by the Eldrazi.

Propaganda art? Welcome Gideon to the 1800s. That changes pretty quick late in the century.

Hero of Goma Fada by Lake Hurwitz, digital

Thompson paints the story of William Brydon struggling into Jalalabad on a dying horse. It almost has a Don Quixote feel to it. Considering he's to be the last survivor of over fifteen thousand people retreating from Kabul in the Anglo-Afghan War, the pity is real. Others actually made it back, but it's a bit more heroic and horrid to show an annihilation of an army with a single figure. You can relate to it as a propaganda piece of wanting to pick up your sword and musket and follow the warrior back into battle to right the wrongs!

Elizabeth Thompson, Lady Butler, Remnants of an Army, 1879, 52 x 92 in., oil on canvas, Tate Britain.

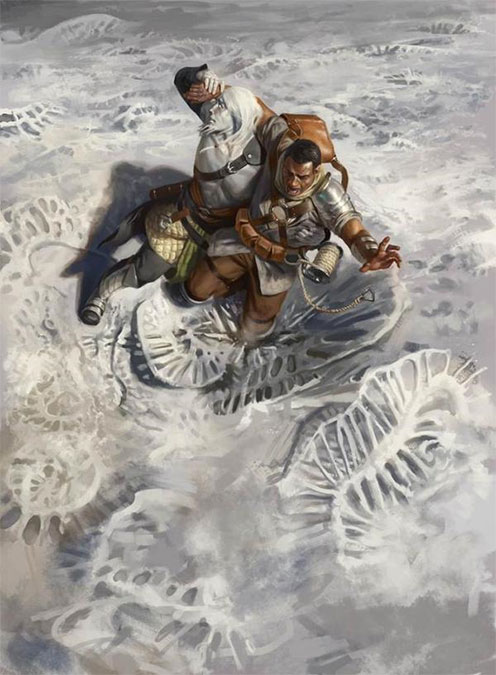

Speaking of being able to relate to a singular survivor after annihilation . . .

It even shows different cultures binding together. You can't make a better poster than this to join an army.

Early 1900s: The Camp and Photography's Disruption

By the time of the American Civil War and the Crimean War, photographers began to compete with artists in coverage of scenes, as photography finally became strong enough late in the century. Their shutter speeds weren't fast enough for battles, but logistics, camp scenes, trenches and the after effect of war became widespread.

Home, Sweet Home by Winslow Homer, c. 1863, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

While camp life illuminates the physical and psychological plight of ordinary soldiers, it takes until after the war ends for painters to dig into the subject matter of boredom, depression, and woe from a war that had no clear end in sight. Photography was just too new to showcase and document the battles. Painters then described the war and the aftermath.

We don't see much of this era of war art in game, but Magic rarely has camps shown. But they don't show the uneasiness of making makeshift shelter with an enemy outside of earshot. It adds to the description of the conflict, though, and I'm happy not all depictions are battle scenes.

World War I ended glory of war in art. It had been in decline for nearly a century anyway, but a mechanical invention made paintings to show historical record, and propaganda just old-fashioned. Also, it turns out mustard gas is pretty awful compared to two lines of soldiers shooting long rifles at each other at designated times like a summer camp's craft softball scheduling.

The Great War, as it was called at the time, had war artists to show horror and also, of course, propaganda. Some artists still fought as soldiers, though, showing their experiences both on the battlefield and showed the Western Front and eerie thousand-yard stares of the earliest post-traumatic stress depictions. Outside of this article, this becomes ubiquitous with photography during the Vietnam War if you want some timeline perspective for how long it takes for photography to be everywhere in war.

Spring in the Trenches, Ridge Wood by Paul Nash, 1917 (1918), collection of the Imperial War Museum, London

Gruesome Slaughter by Aleksi Briclot, digital

Those Sea Gate tents of Zendikar sure take on a different meaning when the psychological effect of a foe completely annihilates your camp. The last image one has is midbattle, as taken from a fast-shutter-speed camera at best and from memory from a fleeing soldier at worst. Look at how aggressive and absolute the Eldrazi victory will become.

Aleksi here is painting us as a war documentarian, painting out the scenes that replay in his head, hoping to gain closure. Survivor's guilt is what artists after World War I carry with them-they don't fight as much, but they are journalists, observers, bound by a code to not intervene.

War art has come a long way from being just showing what happened, to propaganda purposes, to civilian perspective, and finally to gruesome aftereffects. Reading on the photographers of World War II and Vietnam is mighty-interesting and often fast reads if you have any additional interest on this subject matter.

I hope we can do more of these little strolls through art history again in the near future. I'd list more citations, but honestly, look up the art. That rabbit hole will be enough to sustain you for days. I know I've lost sleep reading up on Italian city-state battles and figuring out exactly when Prussia, the basis the Innistrad, became a thing. I implore you to do the same-just make sure you get to see some paintings while you do so!

Thank you for strolling with me. Let's do this again soon.

-Mike