Richard Garfield’s million-dollar idea went from dream to reality within two years, although not without having to overcome some substantial hurdles on the way. One of them was a real head-scratcher: How could they illustrate a game requiring over three hundred individual pieces of full-color artwork? For those who know Wizards of the Coast as the gaming behemoth it is today, that might seem like a cinch. But the company releasing the very first printing of Magic was very different indeed—one that had almost been bankrupted by a ruinous court case, one that had scraped together the investment to launch Magic from all sorts of unlikely sources (and from remortgaging boss Peter Adkison’s house), and one kept afloat by the dedication of a group of friends, straining every sinew to make Magic a reality

It is possible that, had the game been concocted anywhere else in the U.S. in the early 1990s, no satisfying solution would have been found. But this was Seattle—a place where leylines in the burgeoning knowledge economy and exploding arts scene crossed, filling the air with crackling electricity most notably channeled through Kurt Cobain’s screeching Jazzmaster. Here was a city where geeks and creatives rubbed shoulders in coffee houses and concert venues and where, ultimately, an embattled start-up like Wizards of the Coast could entice a generation of young up-and-comers to turn their paintbrushes to fantasy art for the first time. Thank God they did. Because their artwork transformed the game into a feast for the senses, accentuated its radical newness, and imbued it with that all-important yet intangible quality that sells products like nothing else: cool.

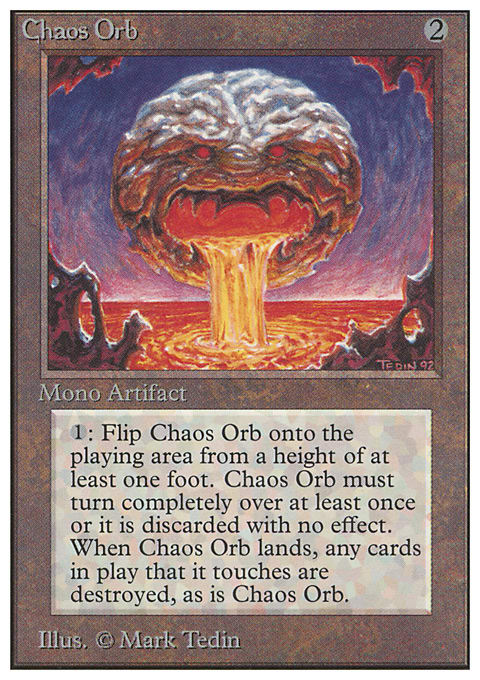

How cool was Magic art? Let me give you an example. Having discovered the game as a teenager with friends in rural New Zealand at the tail end of Revised Edition, I was starved of information on the game. The Internet was something we had only vaguely heard of. Occasionally, we would score a copy of Scrye magazine and froth with excitement over the names of expensive cards in the price guide, despite having absolutely no idea what they actually did. We would trade furiously trying to get hold of older cards—commons from Legends or The Dark—just to uncover a little more of this universe. Then, one day, my best friend Simon won a poster in a games store raffle. It was a promotional item designed by Wizards of the Coast with about fifty or so iconic cards laid out in a giant grid, a little like an uncut sheet, for fans to pore over. The strange thing about this poster, though, was that none of the cards featured had any text on them! No names, no rules text—just the artwork—presumably to prevent primitive attempts at pirating the cards. Did this in anyway lessen our enjoyment of that poster? Did it hell! That thing fascinated us—we would study every detail of every image, looking for clues that might help us match the card in question to a fabled name in the back of Scrye. We would tick off with glee any of the cards we actually saw in the flesh (though only mentally of course—we would never desecrate the actual poster). And we would rabidly ask players older than us for information that might lead to a positive ID of any of the images on the by now well-loved sheet of glossy paper. Magic’s gameplay was undoubtedly great—but we might not have even been playing it correctly. What we could be sure of was its cool factor. Chaos Orb, Time Elemental, Lich . . . all were images on that poster that fired our imaginations and created an emotional link to our new favorite obsession. We were squatting on the floor, slinging our cards, proto-Vorthos kids, falling in love with a world of endless possibility, created by brilliant minds from the same city that the cassettes we were rinsing as we played also hailed from. It was a heady, infectious brew.

Here, then, is a chapter from my new e-book SO DO YOU WEAR A CAPE? The Unofficial Story of Magic: The Gathering dedicated to the artists who helped blow my teenage mind. It has never been quite the same since.

Chapter 6: The Sub Pop of Gaming

If Gencon ’93 [where Magic went on sale to the general public] confirmed one thing, it was that Wizards’ modest hopes for the game were going to need to be drastically revised. Quite what caused the instant public reaction to the game is open to interpretation—the gameplay was undeniably brilliant, but the play-testers had enjoyed the same experience and still only counted on punters buying a deck or two at most. Chris Page, one of the East Coasters who was at Gencon and witnessed the scramble for Magic firsthand, thinks the play-testers may also have underestimated how much people would buy, simply because they themselves had not been able to buy cards: the quantity of cards in their environment was strictly fixed and only via trading could they accumulate new tools for their decks. He also points to another factor that hooked the game’s early adopters: “I think the art added a big part to the game,” he says. “There was certainly a huge difference in seeing the finished cards compared to the play-test cards, which might have had like a black and white picture of an aeroplane or something stuck on them. I wound up buying two boxes worth at Gencon myself.” That would be music to the ears of Jesper Myrfors, who along with [vice-president] Lisa Stevens, had another complex production problem to solve during the game’s development: how does a new company, with very little cash, commission 302 pieces of full-colour artwork for a brand-new type of game?

Myrfors is a towering presence. Part artistic eccentric, with his long mane and black, paint-smudged leather jacket; part Viking, too, a gentle giant with a famously boisterous streak. Born in Stockholm, Sweden, before his father was recruited out of the navy by Boeing to work in Seattle on the 747, he now lives surrounded by Lake Washington’s lapping waves on Mercer Island, a landmass reachable by road bridge from East Seattle, where inhabitants sip strong coffee and live for the glorious moments the sun breaks through the low-hanging cloud. Quite how one small island contains Myrfors’ boundless creative energy, brimming passion and bonhomie is a mystery. But, by common consensus, without those qualities, Magic would have been a poorer product by far. Ask Richard Garfield himself if Myrfors helped raise the game’s production values and you get an emphatic, “Absolutely!” in response.

In the early 1990s, Seattle was the world centre of misfit culture. Grunge music was taking over the airwaves in a raucous whirlwind of screeching guitars and flannel shirts, and reluctant artists were being thrust upon the world as standard-bearers of a new alternative avant-garde. While Nirvana and their Sub Pop stable-mates floored fans with their heavyweight riffs, a new generation of local visual artists was flourishing, too, not least at Cornish College of the Arts. Housed in the handsome 1928 William Volker building on Leanora Street, just over the road from the Seattle Times headquarters, you cannot miss the school: painted in contrasting grey and maroon livery, today its name is stenciled on to the side of the building in huge letters. Contrary to some of their teachers’ expectations, the graduating class of 1993 were instrumental in making that name by deploying their brightly burning creative skills in the service of Magic. “There was just something in the air,” says Myrfors. A student at the college himself, it was he who bridged the gap between the misfits in the city’s creative scene and those striving away in Peter Adkison’s basement.

The young Myrfors was an avid gamer and a huge fan of the fantasy artwork he discovered in role-playing books and board game boxes. His hero was the British illustrator Ian Miller, whose haunting, gothic artwork had helped define the look and feel of wargaming juggernaut Games Workshop. He was also at the time a big fan of the role-playing game bought up by Wizards of the Coast to seal their push into the market, called Talislanta. Having heard rumblings about the game being discontinued, a concerned Myrfors headed to his local game shop, Games and Gizmos in Bellevue, to find out what was going on. There, the staff informed him that a local company had bought the game and would be bringing out a fresh version. Myrfors scribbled down Wizards’ details, popped them into them in his wallet and promptly forgot about them.

More than anything else, Myrfors wanted to be a fantasy artist. His output at college was geared firmly towards his favourite genre, but despite the technical skills he was learning from his most inspirational teacher Preston Wadley, he was getting little practical help on how to break into his industry of choice. With little knowledge of the gaming world, staff at the college pointed him in two directions: Album covers or book jackets. And, they told him, he would have to move to New York or Los Angeles to have a shot at cracking either of those markets. Frustrated but undeterred, Myrfors resolved in the summer of 1992 to not return for his final year at Cornish without a piece of published artwork to his name in the field of his choice.

It was then that he remembered the scrap of paper lodged in the corner of his wallet and got on the phone to Wizards. Lisa Stevens, art directing between her many other roles at the start-up, agreed to look at Myrfors’ portfolio but decided the artwork wasn’t the right look for what Wizards were working on. She did, however, put him in touch with her old employees White Wolf and John Tyne’s Pagan Publishing, and soon Myrfors had his first published fantasy artwork under his belt. Mission accomplished. But Myrfors couldn’t stop there—the Talislanta fan in him would not allow him to.

“How about I do a piece on spec for you?” he asked Stevens. He would do a piece of artwork to her brief and she could then decide whether she wanted to buy it or not. Stevens acquiesced and asked Myrfors to do a piece for Talislanta within a week. Myrfors, eager to impress, produced two paintings in one weekend. Stevens duly showed them to Talislanta creator Stephen Sechi for his approval—and suddenly Myrfors was on board, working on his favourite game, on his own doorstep.

The larger-than-life Myrfors quickly made a name for himself at the Wizards office with his infectious enthusiasm, sense of fun and determination to make great games. Soon, he was attending Wizards’ weekly Thursday meetings and helping out with any odd job he could to cement his role at the company. But popular as he was, he had noticed that he was not invited to a series of secret meetings that the key employees kept slipping off to. “The Project”, as they dubbed it, was off limits to him. But with his usual tenacity, and after doing plenty of grunt work to impress the bosses, Myrfors did one day manage to infiltrate one of the shadowy meetings. Someone thrust a Magic play-test deck into his eager hands. And Myrfors had his first crack at a game that would quickly supplant Talislanta in his affections. The seasoned gamer’s reaction was instant: “I don’t want any money for the work I’ve done,” he told Peter Adkison. “Just pay me in stock.” These little cards were going to change everything. Myrfors could sense it in his bones. But something would have to be done about the photocopied Calvin and Hobbes artwork.

Although the teaching staff at Cornish College knew little about the fantasy industry, they were partly correct in their assertion that book covers and album sleeves had been the main outlet for full-colour fantasy artwork. Although boxed games, role-playing rules books and fantasy magazines were packed full of illustrations, much of it was by necessity black and white—printing in full colour was still an expensive undertaking, particularly for a start-up, and full-colour artwork was normally reserved for high-impact covers, because it was expensive to commission. Part of Peter Adkison’s thinking when he gave Richard Garfield the brief to create Magic, was that there was a stockpile of existing artwork to be mined, produced by artists who, outside of the convention circuit where their work for small gaming companies was on show for hardcore fans, got little exposure. By buying up second- and third-use rights to existing artwork, Wizards figured they could quickly and affordably assemble enough artwork to populate Garfield’s game. But the idea of pasting existing artwork on to such a radical new game, necessarily giving it a generic look and feel, horrified Myrfors. At once artist and gamer, he sensed that the very customisable nature of the game meant that it was crying out for each card to be an individual treasure; to be discovered, collected and curated in its owner’s deck. At once, Myrfors petitioned Adkison to do everything he could to use original artwork.

In his gut, Adkison knew Myrfors was right. But the budget for the game would only stretch so far: the best deal Adkison could come up with for each piece of artwork was $50 cash, $50 in stock and 50 artist proofs (one-sided versions of the finished card which artists could hand out to promote their work). But the key incentive would be a slice of a royalty pool established for the artists—a certain percentage of sales would go into it and the money would be divvied up according to how many Magic images the artists had done. For established artists, it was not a hugely enticing offer. But Myrfors knew where to turn for help: “Peter,” he said. “I can get you the artists.”

Julie Baroh is Seattle born and bred and works today out of an ex-industrial unit in Georgetown in the south of the city with fellow artist Mark Tedin. The young Baroh was a sports-loving tomboy with energy to burn, who in high school preferred cutting class to planning an academic future. When it did become time to figure out her next move, she opted for the local art college, where even with a low grade-point average, she had a chance of scraping in. Besides, she had been drawing since she could hold a pencil and Cornish College seemed like it might be a cool, creative place in tune with her mindset and the prevailing Seattle vibe at the time.

Her first two years were hell. The illustration course she had enrolled on demanded that students first take two years of graphic design, before the illustration component began. That felt excessive and a waste of time to the rebellious young Baroh, who was soon dodging class again and trying to plot an escape route out of the graphics lessons that were dragging her down. Her art student friends, including Jesper Myrfors with whom she had grown up on Mercer Island, Amy Weber and Sandra Everingham, made life tolerable—but when she was unceremoniously booted off the course, she was only too glad to go. She found a place for her talents instead on the fine art programme at Cornish and decided to major in print-making and sculpture. Still, she talked all the time with her friends from across the curriculum and it was not long before Myrfors put the Wizards deal to her—and indeed all his peers at Cornish.

Baroh, along with Weber, Everingham, Andi Rusu, Cornelius Brudi and recent Cornish drop-outs Anson Maddocks and Drew Tucker, all jumped at Myrfors’ offer. Tedin, meanwhile, was a friend of Maddocks’ looking for work after finishing a masters’ degree in St Louis, where his tutors despaired at the doodles of Klingon battle cruisers littering his sketchbook. “To us, it just sounded a lot of fun,” says Baroh. “And Jesper really loved the concept. He emphasised to us what a completely new type of game it was and pretty soon, we were all caught up in his enthusiasm for it.” For most of the artists involved, including Baroh and Tedin, it was their very first paid gig. They took to it with gusto, even if fantasy illustration was not something they had done before, even without fully understanding the game, or indeed, without being fully formed artists. Wizards was their Sub Pop Records: the DIY, punk rock upstarts of the gaming world and the outlet for an alternative wave of new art.

To Myrfors, this was exactly what such a radical new game needed—up-and-coming artists with equally new ideas. “None of them were particularly fantasy artists,” he says. “But I liked that.” For Myrfors, now the de facto art director for Magic’s first print run, variety would be key to the game’s appeal and he would rather include bold art that risked polarising players than re-tread the same old fantasy tropes for the nth time. His other guiding principal was that the art should be recognisable from a few feet away, so that anyone walking past a table of Magic players could spot straight away that they were playing the startling new game. “I didn’t want book covers reduced down to a muddy mess,” he says. “It had to be clean, iconic images.”

The artists Myrfors had contacted (plus some recruited by Stevens from her White Wolf days) went into overdrive—and were soon comparing notes, enthused by the collective buzz of working on a new project together, their first as professional artists. Myrfors remembers doing much of his work while hanging out with other painters watching John Woo movies. Friends such as Mark Tedin and Anson Maddocks would egg each other on. And Julie found herself locked in alien debates with Myrfors about what exactly a blue spell called Clone, her first piece, should like look. It was a creative explosion that turned up fantastic results—and came as no surprise to Myrfors’ mentor at Cornish, Preston Wadley. He remembers the class of 1993 with great fondness and an avuncular chuckle: “I remember the first day we had a homework assignment due and everybody pinned their work to the wall for a critique,” he says. “The gauntlet was laid down. It was going to be the homework wars, I could see that. There was a supportive, nurturing competition within that group and no-one wanted to be the one that didn’t give their best.”

Soon the work was rolling in as quickly as Myrfors could process it on his rudimentary set-up at Wizards: a Mac Centris 650 with Version 2 of Photoshop and a tiny flatbed scanner that restricted everyone’s artwork to the maximum size of 5” × 7”. Myrfors was teaching himself the software on the fly—and along with fellow artist Chris Rush, working on the graphic design of the cards themselves. Rush designed the Magic: The Gathering logo (The Gathering having been added because Wizards were unable to trademark the word “Magic” alone) and the mana symbols for the five distinct colours in the game. Myrfors designed the borders that would frame each illustration and present the card’s title, casting cost, rules text, and power and toughness if it was a creature. One feature he was careful to include was a different texture to each colour of card, so that even colour-blind players could distinguish between them. He also designed the card back, which to this day remains unchanged—just.

While many games previously had used a single illustrator for their components, the impossibility of asking one artist to produce over 300 pieces of colour art was turned into a virtue by Myrfors and the 25 artists he assembled to produce the artwork for Magic. Variety was the key value—and one thoroughly embraced by Richard Garfield. With Myrfors dishing out only the most minimal of briefs, there were few guidelines in place, although it is worth noting that from the word go, female nudity was ruled out. Scantily clad maidens being rescued by beefcake barbarians represented the very worst of generic fantasy art and the misogynistic rut that the largely male Dungeons and Dragons player base had at times dragged role-playing into in the late 1970s. Wizards’ decision was in tune with more politically correct times and signaled their hope that perhaps with a new female-friendly game, women gamers could be reached in more significant numbers.

That rule aside, though, the artists were to give free rein to their imaginations. Baroh worked quickly in coloured pencil to produce cards with names like Clone and Mindtwist, Tedin tapped into his comic book influences for images such as Timetwister and Chaos Orb, Myrfors produced desolate landscapes for powerful special lands such as Bayou and Tundra, while the artist Drew Tucker produced distinctive loose watercolours for cards such as Plateau. Uncharitable souls might have called it a hodge-podge of clashing artwork but the results were exactly what Myrfors and Garfield wanted to see from the game’s art—a wild mixture of bold imagery that reinforced the game’s modularity. They hoped the art would excite players, as much as it did the Wizards staff who hotly debated the pieces as they flowed in. A new gaming form deserved a new approach to the art, says Mark Tedin, who fondly remembers seeing the game’s visual world take shape. “The bonus of having so many different artists from so many different fields and backgrounds, was that there was no pre-conceived notion about what the art should look like,” he says. “It was really rewarding seeing everyone’s different efforts coming together.”

Despite the impact of the art on the game’s early adopters, there is a legitimate question to be asked at this juncture: did Magic need artwork at all? After all, some of the world’s most enduring games are played out with abstract components (such as go and backgammon), tiles or cards organised by suit and number (such as poker or mah-jong) or imagery simplified to the symbolic (chess). In part, their popularity is due not simply to the quality of their gameplay, but because such components are instantly understandable, graspable by players from across continents and cultures—and indeed by those who may harbour prejudices against a specific genre, in this case what in the broadest brushstrokes gets called fantasy.

Indeed, ask most top players today which images adorn the cards in their Magic decks and they probably won’t be able to tell you. While that may say something about the far more homogenous direction the game’s art has evolved in since Jesper Myrfors last worked at Wizards in 2000, it is also due to their focus on the game mechanics of each card, rather than its aesthetic impact. For them, the game could be about cops and robbers, cars or robots. And while some of those themes may have introduced the game to a completely different audience, it is worth noting that however hard it can sometimes be for a 30-something man (for example) to explain to his friends his excitement about a new goblin card, Magic’s genre is intrinsic to its quality as a game. Unlike any of the classic games mentioned above, which are played with a fixed number of pieces, Richard Garfield’s concept for a modular game meant an identity of some kind necessarily had to be mapped on to the cards. Magic would never have been able to grow as per the implications of its design if the cards, instead of being divided into five colours with individual names, were divided into five suits with a number (the five of clubs, for example) like traditional playing cards—it would have been nigh-on impossible to conceive new designs and create the richness of the game (now with around 12,000 unique cards) if each card was only an abstract value. This is particularly true of recent “top-down” Magic sets where cards have been designed to represent a certain theme, like gothic horror in the popular Innistrad expansion, but more broadly, too: creating a game with an infinite variety of pieces means giving each of those pieces an identity. And fantasy was the perfect fit.

“It’s easy to say fantasy is an element of so-called ‘geek culture,’” says [early Wizards stalwart] Skaff Elias. “But it’s not. It’s an element of culture generally. You can walk up to a person in the street who has never played a game of any kind before and ask them what they a think a shield should do versus a sword. They will automatically know that. If you try and think about what kind of intellectual property you can map over a game like Magic, you will be hard pressed to find anything remotely close to fantasy in terms of its ability to convey comprehension.” The monsters fought in fantasy games are largely drawn from myth—and, whatever technological advances we may trumpet in the 21st century, that remains a deeply engrained part of who we, as humans, are.

While Magic may never be as popular as Uno, there is little point in fans of its gameplay banging their head against the incompatibility of their favourite pastime with friends who claim simply not to “get” fantasy. Like it or not, Magic would not be the game it is without its genre.

Twenty years on, Preston Wadley is still teaching at Cornish College. A 61-year-old whose mixed media work juxtaposes found objects and photographs, he is the one teacher the Cornish Magic artists immediately mention as their most influential. Without him, many would never have learned the skills or indeed the self-confidence to produce the work for the game that they did – he is, in short, the spiritual grandfather of Magic art. And like any grandfather, he is immensely proud of how his charges turned out. Batting away any notion that he should take credit for the success of his former pupils, he says that on the contrary, it was easy teaching the group of students who trained their brushes and pens Magic-wards. “They had desire,” he says. “And you can’t teach that.” While Wadley says that Myrfors was the leader in that sense, none of the artists who learned their trade at Cornish and graduated on to Magic would have done so without that same gnawing need to achieve excellence. They were hungry. They were ambitious. And they weren’t afraid of hard work. “Assessing your weaknesses, realising what you have to do to overcome them and making your goals manifest,” says Wadley. “That’s where real talent lies.”

SO DO YOU WEAR A CAPE? is available now: